November 15th, 2020, 5 pm.

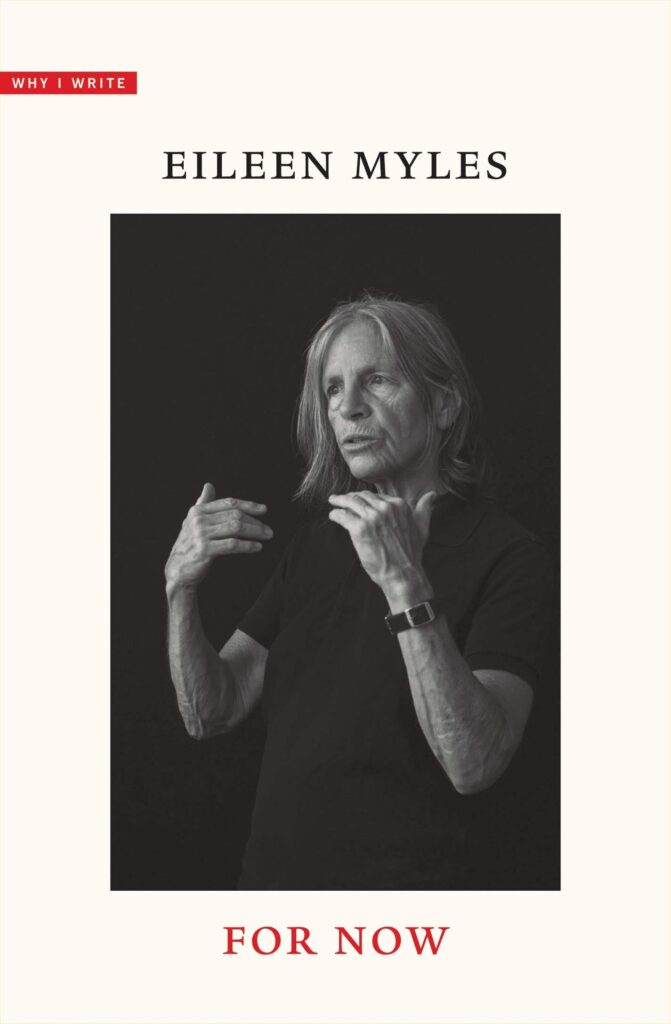

Poet, artist, and polymath Eileen Myles talks with CJLC about queer avant-garde writing, the New York poetry scene of the 70s, the instability of the writerly self, their ambivalent relationship to the archive, and more.

Campbell Campbell:

To get started, I’m just gonna jump the gun and say—I’m interested in you being not only queer but also a writer of queer texts. What does it mean to be queer and a writer of queer texts to you? Does being queer necessitate a queer form, and how do you feel being placed in that genre?

Eileen Myles:

I feel okay about it because it’s sort of irresistible. The thing about being queer is that if that’s in you, or a part of you, or who you are in a way, then I think that culturally we just file that way. I know I’m read more widely by people who are queer. I think, unlike being heteronormative, it gets to be a part of how you’re associated and how you’re arranged. In ways that are wonderful and ways that are weirdly discriminatory. It’s a mixed blessing, and it’s interesting in terms of how I talk about myself [rather than] what I do in my work, because my work is organic and a place where I can make playful and powerful choices. I’ve never regretted the decisions or felt that I had to go in a direction, one way or another, because of who I was. It just seemed part of the apparatus, my queerness.

But I think talking about the work, it’s tricky. The comparison between queerness and race doesn’t really work, but I will say that the “double-consciousness” notion does compare because you’re always thinking about yourself in these two ways and knowing that it’s part of your richness and part of your burden.

CC: How do you imagine a queer form?

EM: I think in the same way that people are increasingly talking about transness, it’s a way of thinking that transness is the root of sexuality. That there’s just a changeableness about human sexual nature. I’ve found perpetually that the most interesting writers, the ones I’ve gravitated towards, are almost to a one—queer. I think that radical form almost “queers” itself in a way. In the same way that historically most of the Americans who have won the Nobel Prize have been alcoholics. What does that say about America or literature? I just think that most avant-garde writing, that I know of, is queer.

CC: I’m also interested in the fact that a lot of your works are autobiographical, whether that’s your memoirs, your poetry, your essays. I’m wondering if your experiences, specifically your queer experiences, are best conveyed in a queer form or an autobiographical text?

EM: I don’t really use “autobiographical” as a description of my work. I was in college in the late 60s, and one of the things going on then was “New Journalism”, which someone like Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, and Hunter S. Thompson. People who were doing journalism in this ecstatic, poetic way. They were busting open the form and notions of objectivity. It seemed very related to the world of film and media that was starting to be really interested in new kinds of documentary filmmaking. I think what happened in the 60s is that people started to throw away notions of objectivity and truth being conveyed in journalism and recording. I think fiction and nonfiction started to blur, it seems to me, in the late 60s and 70s.

I’ve always said this about Chelsea Girls; I was responding a lot to Truffaut, who was the first “art filmmaker” I saw when I was in college. He was doing this fictional account that seemed also an autobiographical account of a young man. And I thought to myself, “Why isn’t there a female version of this?” And so when I started to write, I was probably more interested in making films, but I had no idea how to do that, but I thought about my writing as filmmaking. I thought, “I don’t know story, I don’t know plot, but I can imagine a movie about this moment in this character’s life.” So it just kind of felt like an assemblage. I’ve always felt very aware of the synthetic nature of identity, and that we’re kind of making ourselves up. Our name is a fiction that our parents gave us. And so I never felt very truthy about “Eileen Myles”, but I just thought that I would use them as my character. And so, I never thought of it as”autobiographical”. I thought it was sort of a wry commentary on the self, and someone who had, to my mind, some amazing experiences.

Thomas Mar Wee: Building off of that, you’ve mentioned some writers who have inspired you: the New Journalists, the queer writers that you alluded to, and even filmmakers who’ve influenced you. You mentioned in For Now about responding to the Beat Generation, your friendship with Allen Ginsberg, and I’m curious about how to situate yourself within the broader legacy and lineage of poetry in America. How do you see yourself and position your career within the people who have come before you and the people who have come after?

EM: I feel like the whole notion of schools has collapsed, but I don’t think privilege has collapsed. I don’t know if you’ve seen it, but bopping around Twitter has been this thing that Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young did about the “American Poetry World”, and the reward system. They used some very obvious names like Pinsky and Louise Glück and this real system of…“these two were on panels that gave major literary awards for decades and they were all each other’s students.”

When I came to New York in the 70s I went briefly to Queen’s College. I had no idea what I was doing. I was definitely coming to New York to be a writer, to be a poet, but I didn’t know so much. I knew Ginsberg; I knew Sylvia Plath; I knew Baudelaire; I knew Dylan Thomas. I’d studied poetry in a general literature way in college, and I did a little bit of “in the world” poetry stuff in Boston, but I really had no orientation whatsoever.

So I came to New York. I very briefly went to Queen’s College for graduate school and I was tipped off by the guy who taught the writing workshop there, saying something about “St. Mark’s Church” and that was where denizens of the so-called “New York School” hung out. I had seen poems by Schuyler and O’Hara by then, and I was very excited by that work. It just seemed so vernacular. It seemed like something I had never seen before, except in something like Ginsberg. So I made a beeline to St. Mark’s church and then just became a part of that community. And then a guy named Paul Violi, who was kind of my first poetry teacher, made me a “tree” of all these schools.

It was very: “this is Black Mountain, and this is Beat, and this is New York School” and he told me: “This is our camp because we’re the non-academic school of American poetry, and we’re outsiders, and we’re associated with music and politics and culture outside of the academy.” It was very exciting, and even the teachers who taught there asserted that they were working artists. We didn’t think of it as an institution, and it really wasn’t, you didn’t get accepted, you just showed up on Friday night at Alice Notley’s workshop with a beer and just began. It was kind of remarkable who went to those workshops.

And so, happily, I met all those people. I’m twenty years older now than John Ashbery or Allen Ginsburg were when I met them. I was in my twenties and it just seemed like the world was so open. It was a very small poetry world so that within less than a year of hanging out I was at a party at Allen Ginsburg’s and Robert Lowell was there, and we were like “Oh my God, how did this happen?” You could just move to New York and be in that room. For ten years, I was part of it. I saw Gwendolyn Brooks read. I saw Amiri Baraka read. It was white-dominant. It wasn’t heterosexual dominant, but it was very much that world.

By the time I ran the Poetry Project for a few years, we were interested in “queering” it. It was interesting because the “elders” were queer but the younger ones weren’t necessarily. And I started having my own gay life over here. I’m not really interested in Adrienne Rich’s work. It strikes me as conservative and just a different poetics, and so when she died, it was very funny because I kept getting asked, as an established poet, to write something about Adrienne Rich, and I kept thinking “Yeah, but I don’t have anything to do with Adrienne Rich.”

I think what’s interesting is that we all read across these camps. I think even though you’re in “this camp”, you probably read some people from over “there”. And so when I had the opportunity to curate and edit, I made clear that I had a more diverse taste than the one that I was in. When you look at how publishing and power unfold, certainly in this country, it still is along these lines. “These people are not published by these presses, and these people are not getting these awards.”

I’ve never been nominated for a National Book Award. Not even long listed. It’s interesting, when I was a judge for the National Book Award, I was officially the “other” on the list. Fred Moten was the person I wanted to see win, and I just pushed and pushed and pushed. I had a lot of say in who the finalists were, but in the end, everyone loved Louise Glück. And she had never won a National Book Award. It was so interesting because we didn’t even talk about her. I learned that that’s how things happen: if you talk about something, people can take it down, but if you want something, you don’t even talk about it and it just moves ahead quietly until at the last moment they’re like “Louie Glück! Louise Glück!”, and you’re like, “how did that happen?”

I can’t deny being somewhat of a New York School poet. As for the Beat thing, I had friendships there. Allen was very generous to me as a young poet, and I associated with St. Marks Church and Naropa [University]. Naropa was very interesting; I went there as a younger person and I continue to go there in certain ways. I came from a Catholic background, Catholic school, twelve years of it. So I had an essentially religious education and certainly disavowed that by high school.

What was so funny about that was I arrived at Naropa being a kind of drunk, druggy, young queer. By the time I was a little older and was teaching there, I’d stopped drinking and taking drugs, because I come from a lineage that dies of it, and I didn’t want to die, so I stopped it in my thirties. What I started to realize was that Naropa was a Buddhist art school and that it had a practice. “Practice” is a Buddhist word. Practice is related, in a way, to spiritual practice, but also to art too. I found that it made sense to think of work in terms that engaged with process, and performance, and enactments. There was something about making work that was processive, and that I thought had a lot to do with Buddhism in the way that the Beats were thinking about Buddhism. I was unwittingly influenced by that and then actually influenced.

I’ll also say, growing up I was very interested in Sci-Fi, and I wanted to be an astronaut. I had every desire to be catapulted out of this world in any way possible. As a practicing artist, what I started to think was no, the thing that’s interesting and difficult is to be here. To inventory where you are. Like when a rocket ship takes off, there’s a countdown. The “ten, nine, eight, seven, six”.

As a poet, I love James Schuyler’s work. There’s always an inventory that erupts into a kind of spiritual transition, whether it’s sexual or spiritual. It’s always based on this inventory of what’s there, and then you suddenly can go into a new space.

TW: We’ve talked about the generation that preceded you, but I’m curious what you think about the generation of poets that has come after you. You’ve been publishing work since the 80s, and you’ve accumulated quite a large readership, so I’m curious if you can see the impact you’ve had on poets that have come after you and have been reading your work?

EM: The thing is, lots of them are my friends. I hate the word mentor, I just go crazy at it. I think the older poets that I met, we became friends, and that’s the relationship we had. It wasn’t so professionalized. I met CA when they were in their twenties. They called St. Mark’s church and was like, “do you know Eileen? How can I get in touch with Eileen?” And then I got this phone call.

There’s a transmission that occurs between younger and older poets. The young poet goes to, not necessarily someone older chronologically, but a poet who is someplace they want to be, and you go to this person and you start having a conversation. CAConrad was like that, and Arianna Reines and Michelle Tea were like that years ago. I recognize aspects of my work that are in their work, but everyone always perverts it into a new direction. You’re kind of there to be used in a way and reinterpreted. I think it’s exciting because at some point I realized you don’t ever finish your work. You start things, and it never gets done….In the same way that the audience completes the work, so do the people that are influenced by you.

CC: You mentioned your writing changing, I love the moment in For Now when you say, “don’t hold me accountable for what I say about writing because it’s fluid, and it’s going to change.” I find myself very similarly disliking when people hold me accountable for something I said or thought months ago because I’m constantly changing. What is your relationship to your past writing in light of this idea?

EM: Friendly, sometimes I’m thinking “God I wish I could write that now,” but I’ve changed; I’m not that same person. The way publishing operates you have lots of moments of choice to leave certain work behind and pick certain parts of your past. So there are poems in books that never get in, say, a “Selected Works”. And sometimes I think, “oh, I was wrong, that actually was a good piece of writing.” But usually I feel I’ve chosen pretty well and I feel good about it. Writing prose is different because you make all those choices as part of the process of making the work. You leave paragraphs and pages by the side of the road as you’re constructing the narrative of the book. So it’s brimming with choices, but they’re made. Whereas with poetry, those choices are still out there somewhere. And sometimes, I reread things that I can hardly remember writing [laughs].

CC: How do you think your writing has changed over the years?

EM: I think it’s less personal. There’s less data. There’s less information. I think I don’t lean on information as much. I think it’s become more generalized in a sense.

CC: Why do you think that is?

EM: I guess I have less to prove, I think. I’m more interested in the ways a statement is without specificity. It seems more about movement. The thing about writing is that you want the reader to do a lot of the work. It’s kind of like [Google] “search terms”. Like if I wanted to find this, what word would lead me to that place? In a way, that’s what I’m wanting to do in my writing.

It’s funny, Willem de Kooning had no mind left, and he was still painting, you know. My memory isn’t as good as it was in my twenties. It’s funny because when I was in my twenties and thirties and doing a lot of drugs and drinking, I feel like my mind was so dirty, I had all these shelves and crevices, and I could pack stuff into all these places. And I remember when I got sober I was scared because I felt like this water had rushed through my brain and it was clean. I was like “how can I work with this?” It was working in a clean room suddenly.

I think time does that too. I’ll work on these ideas. You start something and drop it, and I go off and digress with the assumption that I’ll return. My digressions have to be simpler now because I feel like I can’t keep that many balls in the air. I think sometimes it would be amazing just to tell one story that doesn’t stop until I stop. I’ve never attempted that.

TW: You talk in For Now about your relationship to your work being archived, I’m curious if you could elaborate about your hesitance to participate in the archival moment, this fascination with preserving works from writers and having them on display for the public.

EM: It’s just creepy! [Laughs] It’s so weird because you spend so much of your life wanting to be known. All the desires I had when I was younger and at earlier points in my career, for my work to survive and to be known when those started to be realized it just starts to get fixed.

Fans talk to you as though they already know you, and as a writer, I begin to think of myself that way which is when it becomes dangerous. It’s hard. The trick is to get out from underneath your own archive. Writing in journals has come back for me, but it’s different from how it used to be. At this moment in time, Maggie Nelson is my literary executor, and I think to myself, “have I ever talked shit about Maggie in my notebook?” It’s weird to be observed by something that you won’t be around for. You are “post-consumed”.

You constantly have to figure out the new condition: when I stopped drinking, I wondered how I could write while sober. I wondered how I could write queer texts when I came out because, in my twenties, I had various sexual identities but operated in a heterosexual manner. When I stopped, I felt that incredible surge of energy and wrote as a queer person.

There’s always a new mode that you haven’t written in, so this archival moment will fall behind me. It’ll simply be the only writing I have. To be this person who was assuming that my work is being collected.

CC: Do you think that it is an issue with the archive or how people treat the archive?

EM: Both. I think that we are all overwhelmed with the archival question. It used to be, for a while, that every time I met someone and asked what they’re working on, they would say that they’re “working on the archive”. What does that mean! It represents the sheer capaciousness of time and history and our need to save work.

TW: We are all being archived too, with the digital traces that we leave on social media. When you die, Facebook can preserve your account forever.

EM: Exactly. You are leaving traces at every moment.

CC: Do you think, with our heavy surveillance of writers, that there is pressure to over-confess in the text?

EM: Yes, but there is pressure to over-edit too. There is no private moment, and it changes how we disclose information. Everyone talks about how combative poets and artists were decades before me. There was no sense of a career, and you would say shit about people’s work. Now we’re more careful about the traces we leave behind.

I remember when people started to record their poetry readings. People would gossip in between reading their work, and I remember the day we knew that the reading was going to be recorded and put on the internet. Now I have to be less voluble about what I say in the reading because people will hear it. Not only will they hear, they’ll watch me say it! It puts a chill on the community, and that becomes the new normal.

TW: I am curious what your relationship is to Instagram? Do you see it as a part of your work, part of your profession, just a normal outlet?

EM: All of those things. I have always loved taking pictures, and my account has become a public gallery. I showed at a gallery in Provincetown, the Bridget Donahue gallery. Every time I moved into a new genre, there were opportunities for reward and attention. I would like to be oblivious to that, but I realize that my putting pictures on a wall created desire.

You can take a picture and have it identified for its sense of beauty, but there is Instagram where I have no rules and can take more than one picture per day. That is a type of curating which is different from my past experience with it. It is more relational in how the photos are ordered, and it’s also obviously there for publicity needs.

I am obsessed with East River Park and its demolition, and Instagram has become a site of activism for me. It is nice to have a lot of followers who are affected by you. It can be a useful political tool.

CC: You often collapse time in your work. You’ll show your thoughts in such detail that we are exposed to your present interiority, but you remind us that your self is constituted by past experiences and future goals. I wonder how you embody the present in your work and how you balance the acts of seeing, creating and living, writing.

EM: What you said is the description of a writing process. I cannot keep the balance of these acts as a human being because it’s hard to finish a piece of writing and have a particular existence. It’s unsteady, yet writing is how I steady myself.

I was a part-time advertising agent in my past, and a friend, the traffic manager, got me the job so that we could drink and work. I think that writing and living is a form of trafficking.

I’m writing a large novel that I hope to finish in under five years and an anthology. And I’m asked to write short pieces because I’m a known writer. There are all these kinds of writing happening, and it feels like a dog race where you have to let one dog win to finish the other tasks. After I’ve worked for so long, I know that I will not fail and I’ll finish the tasks at hand. I will make sense of the pieces that, as of now, just go go go and run off the pier without an end. There will be an end.

I think that the poetry’s that is the greatest teacher follows that Frank O’ Hara line and goes on your nerve. You write and gain momentum, and you become comfortable writing it and being it. It will abandon you even when you write the work, and I think that editing saves the work as part of a synthetic process.

I wrote poems because I knew “I could be this Eileen for the length of this poem.” I wanted to write novels, but I thought, “how can I write novels if I’m not the same person tomorrow?