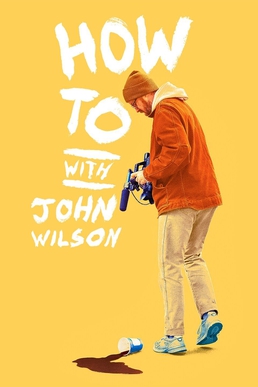

by Charles Smith

John Wilson films normal people. Some are lovers, some are losers and some are landlords. All of them live in America.

His show compiles years’ worth of interviews and street-footage into twenty-minute existential guides to the unavoidable projects of modern life. For example, there’s “How To Make Small Talk,” “How To Put Up Scaffolding,” and “How To Cook the Perfect Risotto.” It is among the most imaginative shows that I have ever seen.

How To with John Wilson makes me want to pick up a camera and film a show that is just like it. John Wilson enters the tradition of great DIY artists, like Bad Brains, Diane Arbus, and Nathan Fielder (who produced Wilson’s show). It is sweet to swallow, bitter to digest. Each of these artists hide their technical and theoretical severity under the appealing gloss of naivety. It takes a master to pull off the illusion of a novice. Whereas Bad Brains condensed their freeform jazz chops into diamond-hard punk riffs, John Wilson uses his innocent, Humans of New York-style premise to conceal a critique of documentary filming in an age of surveillance and paranoia.

The show’s accessibility is due to its extremely low production cost: John Wilson is the only cameraman, and he is also the narrator. Sure, he uses an HD camcorder, but there is no reason this show could not have been done with an iPhone. It is the kind of documentary which is only possible in an age where personal video recording devices are the norm.

Watch footage of New York from the early 1900s, and you will see people swarm the camera or stare with quiet amazement. The act of filmmaking was the event, not that which was taking place at the other end of the camera’s lens. Wilson’s show explores the opposite effect: today, people are willing to ignore the camera, and look into Wilson’s eyes, not the lens, as they try to carry on conversations as though the camera were not there.

Wilson is fascinated with the potentials of documentary film in a landscape where everyone is always recording. His sequences achieve poetry in the playful relation between his narration and the footage on screen. Wilson is adept at finding the affinities between emotion and everyday images–in one sequence, he discusses the fear of opening up and oversharing as a burst fire hydrant erupts. In another, Wilson outlines the typical stages of a relationship, evidenced by street footage of couples of all sorts meeting, kissing, breaking-up, marrying, dying. When I describe this in words, it seems overly tragic, but on screen it carries an element of farce.

Each image, whether mechanical or personal, is universalized upon contact with Wilson’s camcorder. Essentially, Wilson converts his subjects into memes: funny images that are infinitely reusable when contextualized with different captions or different voice-overs. The ease with which Wilson records and pokes fun at these people presents a troubling reminder: if he can do all this with a cheap camcorder, tech companies and governments can do far more. And their objectives do not include making jokes.

As Wilson eventually decides to film his entire life in order to write it off in his taxes, we’re left hoping for the possibility of an intimate relationship beyond the totalizing, satirical gaze of the camera. At rare moments, one is visible–but only in glimpses, only in the gaps.

So, with a seemingly innocent premise to record the quiet beauty of regular life in the city, Wilson stumbles upon philosophical questions: How does the act of recording change our behavior? How are original and copy related? Who controls public space? Where does all that scaffolding come from? How do you make the perfect risotto?

Watch How To with John Wilson on HBO.