Reviewed by Kena Chavva

The catalog of Archipelago Books, a publishing house based in Brooklyn, boasts major giants of world literature: Søren Kierkegaard, Saadat Hasan Manto, Rainer Maria Rilke, Marguerite Duras, Mahmoud Darwish, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Julio Cortázar, the Brothers Grimm, and Aimé Césaire, alongside the names of authors that even well-versed readers of translated fiction might not recognize. Founded in 2003 by Jill Schoolman, Archipelago publishes exclusively fiction translated into English, ranging from languages such as Catalan and Kurdish to more widely spoken and read languages like Spanish and Chinese.

Even a publishing house with the impressive record of Archipelago has its own goals to meet. In a 2017 interview with Lithub, when asked what kinds of authors and languages in which she wants to invest more, Schoolman responded, “I’d like to publish more books from smaller languages, from Indian, Indonesian, and African languages.”

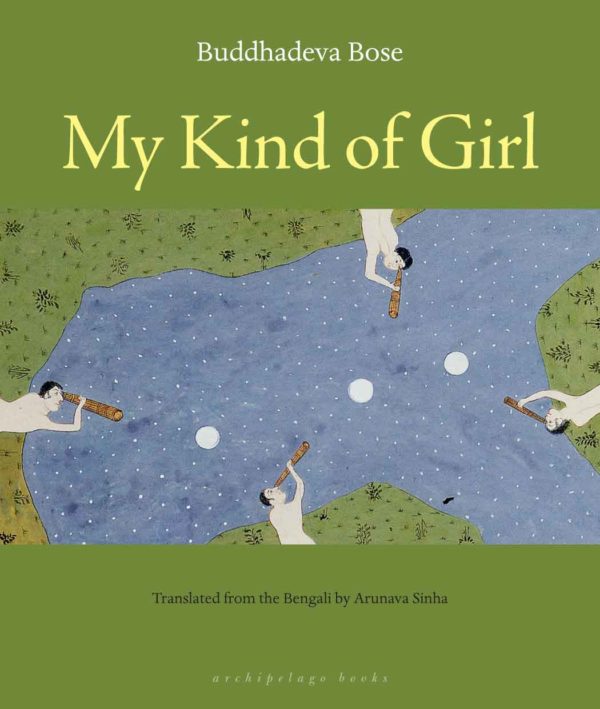

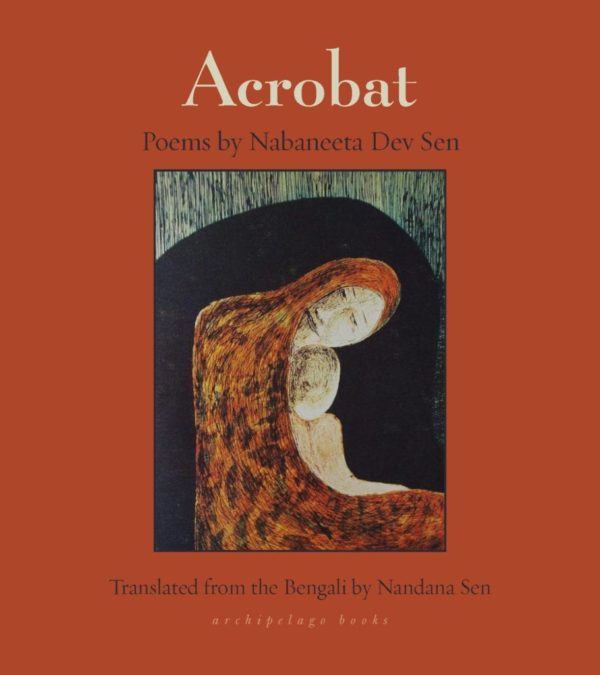

Four years later, just last year in 2021, Archipelago did add a new Indian voice to their catalog: a collection of Bengali poetry by Nabaneeta Dev Sen titled Acrobat. The translation of Sen’s work is the fourth from South Asia in Archipelago’s catalog, and comes nearly a decade after Archipelago’s first translation from Bengali: a novel by Buddhadeva Bose, titled My Kind of Girl, published in the original Bengali in 1951 and translated into English through the publishing house in 2010.

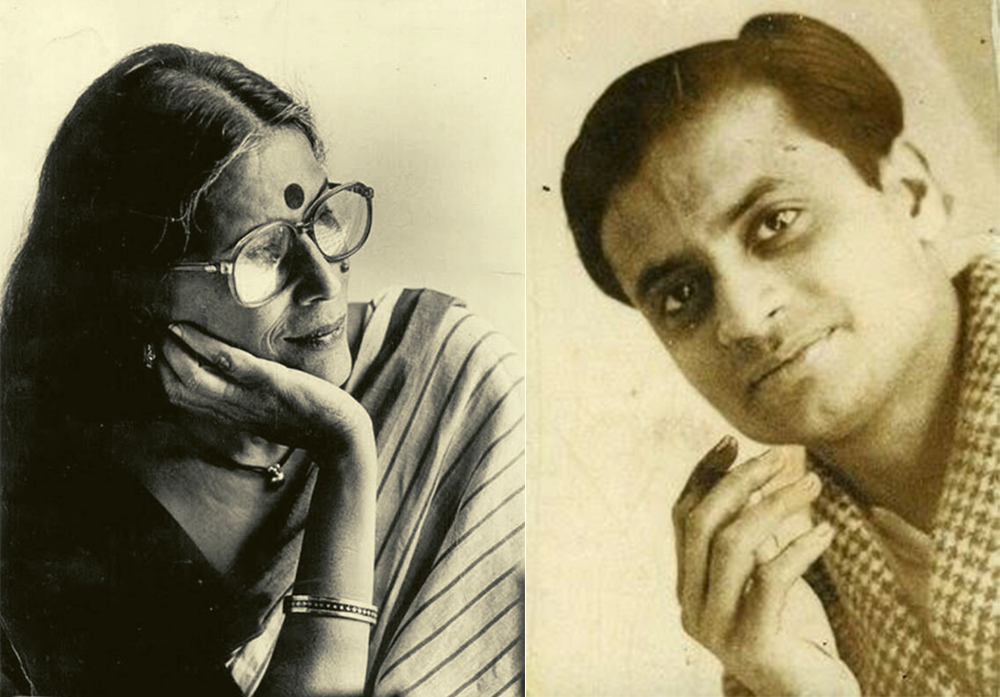

These two translations make a small sliver of the work of two giants of Bengali (and Indian) literature accessible to English-language readers, and a brief glance at the illustrious careers of the two authors reveals a lengthy list of accomplishments and awards. Both Sen and Bose won the Sahitya Akademi Award, in 1999 and 1967 respectively, an Indian award given in recognition to those writers writing in any of India’s officially recognized languages. In 1970, Bose won India’s Padma Bushan award (the third highest civilian award) and in 1999, Sen won the Padma Shri (the fourth highest civilian award). Their literary output was not limited within the geographical bounds of India, either. Bose was a good friend of Henry Miller’s, and translated Baudelaire and Rilke into Bengali. Similarly, Sen was a scholar at Harvard and Cambridge before returning to live in Kolkata permanently.

When reading any excellent new translation, one particular question inflects the experience: why hasn’t this been translated sooner? Given Sen and Bose’s extraordinary acclaim within India, and their connection to the Anglophone literary world—unfortunately still a consideration when exploring why an author succeeds on the stage of world literature—why have they not been more popular on this same stage? It is, of course, difficult if not impossible to fully explain why some authors reach certain heights of prominence and others don’t. In the particular case of Sen and Bose, however, one possible answer lies in the history of modern Bengali literature.

The work of Sen and Bose is indebted to, and pays direct homage to their Bengali predecessor, Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore plays an outsize conception in the western conception of Bengali literature and Indian literature, but simultaneously his reputation has come to signify a kind of nationalism and unity within India (even though his own views on Indian nationalism were complex and do not cleanly map onto today’s political movements). Though Bose and Sen acknowledge Tagore’s imprint on their work, their literature refuses to conform to the desires of Anglophone and Indian hegemonies.

Tagore is arguably the most well-known Indian author internationally. He penned the Indian national anthem “Jana Gana Mana”, and is often referred to as the “Bard of Bengal”. His importance stems from his position as a harbinger of modernity, both politically and artistically: just as he advocated for Indian independence during his lifetime, he also was the forerunner of the Bengali modernism movement, which sought to move away from classical structures of poetry and invent something new—a movement that occurred in other languages across the subcontinent as well. He was the only Indian to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, for writings in both English and Bengali. To Western audiences, he is often flattened into a purely romantic poet (as evidenced by Audrey Hepburn’s popularization of his poem “Unending Love”). This kind of double position that Tagore occupies—that of the national Indian symbol and the sentimental Eastern author—is one that both Sen and Bose contended with as Bengali authors following his enormous influence and from which they ultimately diverged.

Sen was born in 1938 to two poets, Radharani Debi and Narendra Dev, with personal connections to Tagore. She began writing at age seven, and throughout her life, she experimented in all genres: scholarly writing, poetry, and prose ranging the gamut from fiction stories, essays, travel writing, children’s books, and journalism. Sen’s first name, Nabaneeta, was bestowed by Tagore himself, and the cover of Acrobat is of a Tagore painting titled “Mother and Child”. Though Sen had close personal ties with Tagore, Bose’s relationship to him within the Bengali literary canon more closely resembles that of a literary successor; the two overlapped for a much greater period of time, and Bose’s literary output, which was primarily composed of poetry and fiction, similarly looked towards post-independence modernity in India. Despite these similarities and ties, however, both Sen and Bose’s literature move away from the caricatures that Tagore has come to represent in unique ways that unsettle both India’s conception of itself and the Western conception of India.

My Kind of Girl embodies the characteristic struggle between modernity and tradition within Bose’s generation of writers. The novel uses a frame narrative: while waiting for a train, four strangers—a contractor, a government official, a doctor, and a writer—see a young loving couple and are reminded of their own youthful loves. In order to pass the night, they tell one another these stories, which take bittersweet, often hilarious shapes. The shy contractor narrates a “friend’s” love story instead of his own, and the writer tells the tale of interactions with a girl that he and his two childhood friends all loved.

To a reader familiar with contemporary American fiction, the author most similarly working in the same tradition as Bose is Jeffrey Eugenides. Eugenides writes, in his introduction to an edited collection of love stories, My Mistress’s Sparrow Is Dead, that great love stories revolve around “voyeuristic longing and disenchanted entanglement”. In My Kind of Girl, the premise of the writer character’s story, and indeed, the premise of the entire novel—elaborate fantasies blossoming from a brief glimpse of someone—evoke the boys in Eugenides’s first novel, The Virgin Suicides, dreaming of the Lisbon sisters next door.

The physical copy of My Kind of Girl, however, reaches centuries further back into the Western canon to identify influences: the front and back covers of the novel invoke the cyclical stories of Chaucer and Boccaccio in relation to Bose’s work. Wistful memories and remembrance shape the novel, not in terms of only memories of love and infatuation, but of an earlier, pre-independence India (or, in the context of the novel, the moments before the train arrives). My Kind of Girl was published in the original Bengali three years after Indian independence, and takes a guarded view of the future’s relationship to the past, that translator Arunava Sinha renders beautifully into English: “I was thinking—I was thinking, this walk is lovely, but it’s because we’re walking on it that the road will end….Our existence is like that: living eats into our life, and all the roads we love end because we take them.” The novel lacks a translator’s note, and thus, an argument from Sinha that might situate it more directly within a post-independence political framework. However, the underlying sentiment is clear: My Kind of Girl, unlike the popular work of Tagore, refuses to romanticize the future of independent India. Instead, the text waxes nostalgic for the simplicity of the past, while recognizing that the train’s approach cannot be stopped.

Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s poetry collection, Acrobat, in contrast, is a lifetime’s culmination of poetry from Sen that takes pains to anchor itself deeply in her life and resultantly, her present historical moment. The collection was translated primarily by Sen’s daughter, Nadana Dev Sen, though several of the poems were translated by Nabaneeta Dev Sen herself, some were originally written in English, and one poem was translated by her other daughter, Antara Dev Sen. The collection is bookended by two notes from Nandana Dev Sen: an official translator’s note that outlines her approach to translation alongside a sketch of her mother’s career and a letter to her mother at the end (Sen died in 2019, before the collection was finalized).

Acrobat refuses to cleave to the false dichotomy between the personal and the political. It is divided into four sections, titled “The Unseen Pendulum”, “I Cage Language”, “Sapling of a Heart”, “Do I Know This Face?”, and “Sacred Thread”, but these designations are loose, and it is clear that certain themes across sections have preoccupied Sen throughout her life. Poems like “December 1992” and “Festival” address political and religious violence between Hindus and Muslims in India (and Bengal more specifically), while “Take Back the Night” and “Growing-up Lesson” address sexual violence.

Most fascinating, however, is Sen’s ambivalent approach to motherhood, especially considering how closely involved her own daughters were with the process of translation and publication. “This Child”, “Puppet”, and “Umbilical Cord” all grapple with the complexity of being a mother—of being not just a creator of life but also a creator of death. In this way, even more so than her explicitly feminist poems, Sen gives rise to a genre of women’s writing that truly fleshes out the nuances of women’s lives and grants them space, and thus, importance.

The collection outlines a political approach to language as well. Nandana Dev Sen, in the translator’s note, explains that Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s decision to primarily write in Bengali was an extremely conscious one: “She saw this dilemma as a crisis of loyalty, and of identity—not only because she belonged to a generation of writers who rejected the colonizers’ language, but even more critically, because she was deeply worried about the future of regional languages and literatures in India.” Translation, then, for Nabaneeta Dev Sen, was an act that prevented the subordination of Indian culture on an international stage to the Indian writer writing in English, and instead allowed for a multiplicity of Indian identities to thrive (an idea she explicated at a conference on “International, Poetry, Translation, and Language Justice” at Columbia in 2017). Mirroring the arc of Sen’s career—from Bengal to America, and then Britain, and back to Bengal—the last poem in the collection is titled “Return of the Dead”, and is addressed to the city of Kolkata. This particular representative body of Sen’s work, then, upsets both the state-approved image of India by criticizing this society’s attitudes towards gender and religion, but also upsets the power dynamics of world literature by insisting on the importance of regional languages.

Perhaps, then, this is one answer to the question of why Bose and Sen have not been translated into English sooner, and more prolifically: their work deliberately disrupts a particular image set forth by Tagore of Indian and Bengali literature. Of course, this then makes the translation of their work more urgent; just as Sen described, translation allows for the proliferation and complication of identities. In these two translations, at the very least, Archipelago begins this process in allowing the reader to expand their understanding of Bengali literature beyond just Tagore and providing two poignant entry points into a rich literary tradition.