Reviewed by Molly Wagschal

As the world grapples with the repercussions of human-driven climate change—vicious wildfires, harsh temperatures, destructive storms—literature may be exactly what we need to reflect on our precarious relationship with the planet. Rosalía de Castro (1837-1885) was a poet from Galicia, in Northwestern Spain, who was concerned, among other things, with the dynamic and often problematic relationship between humans and the natural world. Castro was one of the only women writers to enter into the 19th-century Iberian literary canon, although not without controversy nor scholarly neglect. She is considered an influential figure within the Galician Rexurdimento (Renaissance), a 19th-century romanticist literary movement that promoted the use of the Galician language to foster a uniquely Galician literary tradition. In her poetry, Castro writes of loss, loneliness, and a longing for connection.

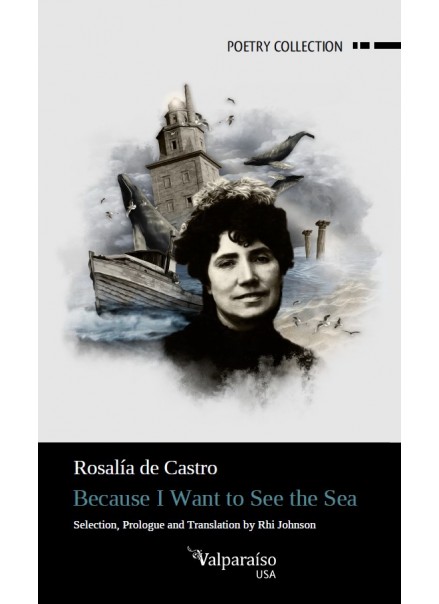

In her recent translation, Because I Want to See the Sea, Rhi Johnson, a professor of Spanish literature at Indiana University, curates and translates a selection of Castro’s poetic work that spans her five collections, written in Galician and Spanish. As Johnson acknowledges in the prologue to her translation, Castro’s poetry has already been translated several times; Johnson distinguishes herself by creatively organizing the poems “to let narratives and ideas weave themselves together” rather than following the original order of the works. The ordering of the poems seamlessly guides the reader through Castro’s existential curiosity, hope, and despair.

The natural world plays a major role in Castro’s poetry, especially the rivers and seas of Galicia. As Johnson writes in her prologue to the anthology, “For Castro, the sea is always lost love, lost lovers, lost life. It is also a motif for death and the locus for suicide. And it is life. Jubilance. Joy”. This paradoxical nature of the sea and, more broadly, the natural world as both a source of optimism and despair is central to Johnson’s compelling translation project, which aims to put Castro’s poetry into dialogue with contemporary anxieties such as the destruction of the planet. Johnson writes, “This anthology is for now; it is for a world being ravaged by climate change and shadowed by authoritarianism; it is for us who live in the Anthropocene but root ourselves in the crumbling soil to hold it and ourselves together”. The challenge of Johnson’s translation project, then, is how to make Castro’s oeuvre legible to a 21st-century American audience while respecting and preserving the particularities of her explicitly Galician writing and identity.

It is clear that Johnson has made a concerted effort to let Castro’s voice shine through the translation, following Castro’s Spanish or Galician syntax and subject-verb order even when it might sound unnatural in English. However, I find that Johnson’s translation best stands on its own when it strays away from a strict, formal translation of the verses and finds natural, poetic solutions in English—what Eugene Nida would call “dynamic equivalence.” One of the most moving fragments of the anthology comes from Castro’s collection, Cantares Gallegos (1863). Translating from Galician, Johnson writes, “Roll on, river, roll on, / with your endless soothing rush”. Johnson could have used several different synonyms instead of “roll on,” for example, “flow”, “run,” or the more literal “pass.” However, the image of the river “rolling on” is at once mystifying and beautiful in English, especially when combined with the alliterative “rush.” It even brings to mind the distinctly American song “Proud Mary,” originally recorded by Creedence Clearwater Revival and famously covered by Tina Turner, with its line, “Rollin’, rollin’, rollin’ on the river.” The movement of rolling in Castro’s poem also complements the poetic voice’s anxiety over her destiny and the loss of her lover, an anxiety she makes clear in the final verse: “but this sea, it has no ending; / oh my love, where then must I go?”. Just like the river, her love has rolled on, leaving the poet behind.

Throughout the bilingual edition, Johnson closely follows Castro’s original syntax, while making small adjustments that make her work speak to a decidedly 21st-century audience. In the first poem, Castro writes “Crea el que cree…,” (literally “Let he who believes believe”) using the third person singular masculine pronoun “el.” In English, Johnson adopts the gender-neutral third person plural, translating the verse as “Let them believe who believe…”. Although Johnson does not address decisions like these explicitly, this small alteration creates a sense of gender inclusivity that helps the poem speak more to a contemporary American audience, a goal implicit in Johnson’s introduction. Although minor in the grand scheme of the translation, a few scattered editorial issues—for example the inclusion of the word “sol” (“sun”) which is left untranslated from the Spanish version with no explanation, and several typographical errors in English—lead the reader to wonder which choices are stylistic and which are unintentional.

Although Castro’s poetic work is grounded in a specific time period (the 19th century) and a specific place (Galicia), Because I Want to See the Sea reads as a refreshingly contemporary reflection on humans’ relationships with the planet and with one another. It speaks to our fundamental anxieties surrounding artificiality and loss of connection, especially in a time when the pandemic has altered our connection to the natural world and to each other. Johnson masterfully curates and translates Castro’s poetry in a way that reaches into the consciousness of 21st-century America while also drawing attention to a critically neglected woman poet.