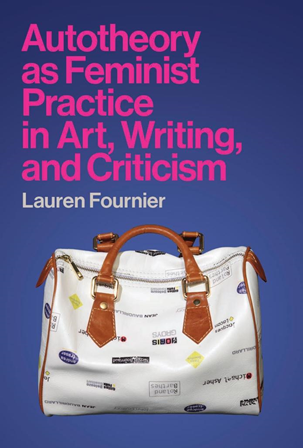

CJLC Editor Rayna Berggren interviews Lauren Fournier on her new book Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism (MIT Press, 2021). To Fournier, autotheory, or theorizing one’s own life, has both a deep historical lineage and potentially reparative future.

Lauren Fournier is a writer, curator, and filmmaker who writes hybrid genres, autotheories, autofictions, nonfictions, and fictions for the page and the screen. She is a first-generation university student/scholar and a white settler of Eastern European and Slavic (Romanian, Ukrainian, Czech/Bohemian, Hungarian), Turkish, Scottish, and French descent raised on the lands of Treaty 4 territories in Saskatchewan. Her book Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism was published by The MIT Press (2021), and has been featured and reviewed in such venues as The Los Angeles Review of Books, High Theory, Contemporary Women’s Writing, and Art in America; it was also included in the Chicago-based Seminary Coop’s list of Notable Books of 2021. She is the founder and director of Fermenting Feminism, a site-responsive curatorial experiment that has featured over 100 collaborators globally. Currently, she is writing about settler colonialisms, microbes and ecologies, intergenerational class mobility, and the vagus nerve, while fermenting things in her kitchen. She is also finishing writing her second book on autotheory.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

August 6th, 2021, 3pm

Rayna Berggren: I want to begin by asking about your autotheoretical practice, especially because Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism incorporates its own sections of autotheory. How did you first come across autotheory and what drew you to it?

Lauren Fournier: I was partway through my PhD work in English Literature when I found that a lot of the writings I was gravitating toward were by artists and writers who tended to work in ways that were generically unclear. Writers who didn’t fit into prescribed categories of genre, discipline, or form.

I knew I wanted to write on the relationship between “bodies” and “texts.” During my Masters, I had engaged with auto-ethnography as a way of writing about performance art and my own art practice. My comp[rehensive] exams were in 2015, the same year that The Argonauts [by Maggie Nelson] came out with the term autotheory borrowed from Paul B. Preciado on the back book cover, popularizing the term and sparking a wave of interest in what autotheory might mean. The whole aim of my dissertation, and now book, was to write a longer history of this term. I chose to do so within the context of feminist critical-creative practices broadly conceived, including conceptual art and video. So, performance and body art by Adrian Piper and Andrea Fraser, video and film by Thirza Cuthand and Hiba Ali, essayistic writings by Audre Lorde and bell hooks, public talks by David Chariandy and Maggie Nelson, sculpture, sound, installation, and so on. I also spent time doing close readings of two white feminist books that had been most often associated with autotheory in contemporary art spaces (The Argonauts and I Love Dick) to really push at their limits and understand the political, epistemological, social, and moral implications of those texts in a larger autotheoretical field. This was, in any case, my aim.

My hope is for my book to be a starting place, an open project, a weak theory, that others might take with them, adapt, and use. That’s what it was, for me: my starting place. I’m already deep into my second book on the topic. In the first, I focus on Anglophone literatures and art: the works I engage with are transnational yet limited to the English language, one limitation of the book that I’m clear about in the outset. This is one reason why I’m so excited about a special issue of ASAP/Journal on autotheory and decolonialitythat I edited with my friend and colleague Alex Brostoff, which features translingual scholarship, including multiple contributions on Gloria E. Anzaldúa’s Spanish-language work, including her lesser-known writings and archival documents. It also features an entire section on critical university studies, with contributions by writers like Che Gossett. It will be launching in the coming months.

It’s an interesting thing, to write about something that is very much in-process. I wish I could have left some blank pages at the end, for people to write in the names of books and other texts that continue to be published or exhibited and that fit the autotheory bill. Some of my favourites, from the past year, that I might add: Karla Cornejo Villavicencio’s The Undocumented Americans (an account of her experience as the first undocumented immigrant to attend Harvard) and Magda Cârneci’s Fem. I’m looking forward to Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes, which seems to be an autotheory of memorialization, and Mithu Sanyal’s Identitti, the German-language novel whose English translation will be out in June 2022 and which takes up the growing problems of people faking BIPOC identity. The “canon” of autotheory/autofiction is ever growing and it’s so dang exciting to bear witness to and to be a small part of. Honestly, I felt quite lonely and in my own head for much of the process of writing my dissertation, which became my first book. It’s only been in this year following its publication that I feel I’m part of a community of folks interested in these practices and ideas. I’m really thankful for that. We all need community.

RB: I’m thinking about the tropes that have already been established within autotheory, of combining self-writing with a more communal citational practice. What’s desirable about the tension between those two things?

LF: Autotheory is most simply, the combination of autobiography and memoir with theory and philosophy (as practices of theorizing, of philosophizing). That self/other form recurs in autotheoretical writing—the form of a memoir or personal essay alongside footnotes, endnotes, marginalia, research. It follows in an academic tradition with bibliographies and citations while expanding beyond it and transforming it. It opens up not only what memoiristic work can be, but also what academic work can be.

I believe there is something productive politically, aesthetically, even ethically, in bringing self-writing and citations together. What happens when they are placed side by side (Sedgwick’s “beside”)? It’s an attempt to ground one’s writing in oneself while also looking outside of or beyond that self. It is understanding the consequentiality and stakes of the personal, but also the limits of that personal “self.” The self is always already relational, always already in excess of that self.

Notably, it has been writers of color, queer/trans writers, and women writers who have come up against charges of solipsism and narcissism within Western, colonial art and academic spaces. These are writers who have been historically overdetermined by limiting conceptions of the “personal,” as if their work is inherently subjective and embodied or “marked” while the work of white, cis men is “neutral” (which, of course, we know is not the case). It becomes all the more complicated, then, when these writers engage directly or explicitly with themselves in their work. I talk about this in my book in relation to the Bay Area painter Christine Tien Wang and a review of her work in Los Angeles by art critic David Pagel.

Citations serve a range of functions in autotheoretical work. It can be a way for writers to “legitimate” their life-writing or to provide evidence for whatever that writer is theorizing from their life and to show that this idea is not only coming from them. This might be seen as a reinscription of the hierarchy of knowledge and legitimacy within scholarship that autotheory as an impulse is trying to resist; but another way of seeing it might be as an energetic exchange of lived experience and the experiences of others, as “lateral citation.”

When I spoke with McKenzie Wark about the book on the MIT Press Podcast, she did note that autotheory as a genre has already acquired certain tropes—one being the way it bridges self and other through the “auto” plus “citation” form. She wondered whether her own book, Reverse Cowgirl, takes part in that. I don’t necessarily see the establishing of such tropes as a problem. These are the early days of a new wave of the genre, and like any genre, there will be certain codes and conventions that take shape. I do think it’s exciting when writers experiment with new, yet-unconsidered possibilities for form.

We’re in such a moment right now, with autotheory and its related yet distinctive term, autofiction. I’m already working on my next book, which engages “auto,” “theory,” and “fiction” as constellating terms. I see autotheory as a practice of engendering knowledge from the work of critically processing one’s lived experience alongside other forms of knowledge, including research and relationships. It’s a practice through which one can take seriously their life and embodied experiences in the world as a source of philosophical knowledge and insight—material through which transformative stories can be told.

RB: You apply Eve Kofosky Sedgwick’s concept of reparative reading to autotheory, especially when it comes to contemporary feminism and decolonial efforts. How is autotheory potentially reparative, in your eyes?

LF: I was thinking about Sedgwick as I wrote, since my very first exposure to autotheoretical writing was through Sedgwick’s work and the work of other affect theory, like Sara Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology or Sianne Ngai’s Ugly Feelings back when I was doing my Masters in Literature and struggling through my own mental health issues, suppressed trauma, and feelings of alienation as a first-generation student who witnessed various moments of classism in the university. This lineage of what is sometimes called “queer feminist affect theory” tends so often to be autotheoretical in its sensibility and orientation, if not its form, and it was by virtue of what I was exposed to in graduate school that this lineage became my first entry-point into what I now understand to be autotheoretical writing. (It was in my graduate seminar on Eve Kosofksy Sedgwick’s work at UBC (2011) that I also realized I was a closeted bisexual!).

I have argued that Sedgwick wouldn’t have been able to get away with publishing autotheory had she not first established herself as a 19th century literary scholar of Henry James. It was after she had established that “legitimate” positioning for herself as a scholar that she could write about desire—not in a sterile, scholarly way, but in a lucid, personal way, a way that sees herself and her own disclosures (like her still-contended identification as a “gay man”) forming not the margin, but the humming center of her argument. The personal was the way of thinking through queerness, pedagogy, intimacy. Sedgwick offered the reparative as a practice of reading that was different from the “paranoid” forms, like Derridean deconstruction, which in the wake of French post-structuralism had become the de facto mode of literary scholarship in North American universities. The irony is that I came to perpetuate this in my own work, writing my first book in a way I understood to be more safely and straightforwardly academic, before I could really write from my own autotheoretical perspective (which I believe I’ll get closer to achieving with my second, forthcoming book on autotheory) and personal political leanings, which take a more revolutionary approach to dismantling colonial structures. In my second book I have sections on “cognitive imperialism” (from Leanne Betasamosake Simpson) and what I call “intellectual reparenting.”

When I teach, I have a conversation with students early on about different ways of reading. Reading as a form of attention. Why do we read? What do we “get” from reading? To deconstruct the center from the margin, as Derrida taught, by finding the text’s internal logical inconsistency from which the entire text can fall? As people with limited time and energies to use here on Earth, might we read to see what we can take with us from a text, how we might be changed by a text, how this text might apply to our life (or not)? To understand how we can find a text’s problems and problematics while also seeing what is working and what we can “take” and learn from? A reparative mode is desirable to me for these reasons. Paranoid readings are easy, today.

In contrast to social media platforms like Twitter or even, despite its slightly longer space for text, Instagram and Facebook (“Meta”), longer-form autotheoretical work allows for taking the time to work through an idea with others. Sometimes, this leads to nuanced writing, to a rejection of binary thinking and an embrace of categorical murk for a potentially productive social, political, aesthetic, or ethical purpose. I noticed that Maggie Nelson’s recent book On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint (2021) (which I haven’t yet read) has been critiqued for precisely this very indeterminacy. This, because her indeterminacy has logical inconsistencies (as Andrea Long Chu observes), and because the writing is seen to be too scholarly and waffly around what concepts or ideas Nelson actually puts forward as a philosopher. And so, perhaps, ambivalent and indeterminate writing too has its limitations. Eventually, we have to say something, right?I am interested in what kinds of things autotheoretical work has to say.

RB: You quote Jennifer Doyle that experience “is not an unquestioned zone of personal truth to which one retreats but a site of becoming, of subject formation.” What are the potential consequences when one’s life experiences become open to critique, either in autotheory or on social media?

LF: Thinking about that Doyle quote, the first thing that comes to mind is the undergraduate art student experience. You bring in your precious memories, personal material into an artwork and then you go to a critique and all of a sudden it’s part of the work and up for literal critique. Defensiveness can understandably crop up. What is more dear (and infallible?) to you than your life and lived experience?

Not everyone is interested in engaging with their lived experience in their work, nor is everyone able to. There are certain stakes and risks in bringing in one’s lived materials, and so this needs to be considered by context. It’s risky to write about lived experience in different ways for different people. I recently taught a graduate course on autotheory and autofiction to MFA students. The class was divided almost in half by those who felt little risk in disclosure of personal materials and reflections—“I disclose everything on the internet! I am an open book!”—and those who were more resistant to writing about so-called personal material. Part of this divide happened to be generational (gen-z and millennial vs. gen-x).

One student admitted to the group that they never write anything personal down, even in a journal, because that makes it real even for them, and they don’t like that. With that said, I was surprised to see how, by the end of the class, everyone was writing in autotheoretical or autofictional modes; based on their written reflections, they seemed to have gotten something valuable from the experience. We were lucky to have a close-knit, trusting class, and a safe space to experiment with what the “auto” looks like across their varied practices. I made it clear that no one is ever obliged to write personally or with their “self” if they don’t want to. The fictional is always there as a space they can turn to.

Doyle’s point gets at the fact that, once you are working autotheoretically, with the materials of your life, those materials are now up for critique. This is a discomforting prospect for someone who wants to make art about their experience without it being critiqued. (In this case, I think the artist likely needs more time to process in their work, and to figure out the right form through which the work can be made.) Does criticism have limits? Doyle notes that “critics have limits”—she discusses how what is difficult for one person might look very different from what is difficult for another (for her, it is one-on-one intimacy that is difficult in the context of performance art, but she has no issue with gore, self-violent art, extreme art).

RB: That fear of stabilizing life experience is very interesting, especially when thinking about the queer and feminist roots of this form. Queer people have a unique relationship with change which might make the prospect of writing something down and freezing a moment in their lives especially frightening. How does autotheory address or exacerbate those anxieties?

LF: Recently, I heard a comedian say, “It should be illegal to get married before you turn 30.” And lately I’ve been thinking it should be illegal to publish personal writing until you’re 30 [laughs]. Or maybe 33! I turn 33 in a few months, and I hear that’s when things can really come together.

I look back at a lot of my writing in my twenties and think, this is pretty cringe. The writing isn’t problematic or anything—it’s just cringe in its maudlin tone, and its uncritical self-indulgence of certain affects and experiences, it’s lack of maturity, really, despite my being told by the much older men I’d been in relationships with at age 19-23 that I was “ahead of my years.” (Ahem) This is writing without the processing power of distance and time (comedy, after all, is tragedy plus time… and I’m a big proponent of tragicomedy). That earlier work needs substantive editing—I’ll just say that. I’m sure I’ll probably feel that way about what I’m writing now in 5, 10, 20 years. Maybe even in 2 years. Look how much the world has already changed in the last 18 months! It’d be concerning if we weren’t changing too.

So yes, I do think it’s important that we’re always growing and changing and evolving. We’re able to, as you say, stabilize certain things or materialize certain things, but still hold space for malleability and flux. If we’re not changing, we’re dying, or at the very least stagnating. I can’t imagine trying to live in such a state. When you’re in a relationship—that changes you. When you experience grief—that changes you. When you go through a move, or a career change, or a global pandemic—that changes you. When you read a book or watch a film that is impactful—that changes you. When you heal trauma or end certain cycles—that changes you. Each beginning and middle and ending changes you.

RB: I’m thinking of your section on The Argonauts, and the role of that book in the larger discussion about trans subjectivities. It raises the question of the zeitgeist: what story is yours to tell? Do you think that is a useful question? Is it something you consider while you’re creating?

LF: That is a very good question! And it’s one that I don’t necessarily feel I have the answers to, but that I think about often both in my own writing practice and from a scholarly perspective. As artists and writers, we do have a gut-based intuition or drive towards a certain project, and the sense of, “Okay, this is something that I feel compelled to think about and spend time on and write for whatever reason.” I think if it stays with you long enough, it’s worthwhile to follow through on that. Sometimes it’s painful not to. Have you had that feeling, when you know you have to write something, otherwise you might implode?

But that gut feeling needs to be healthily countered with an ethical consideration. Is anyone going to be harmed in the writing of this? As writers, I think it is useful for us to devise formal and logistical strategies together to avoid and/or diminish harm. Literary harm reduction! What might that look like? Could we as writers put together a literary harm reduction kit?

This is where autofiction comes in, historically—the roman à clef, the long history of thinly veiled fictionalization, for purposes of avoiding libel and slander and other logistical nightmares. You might change some names, but those who know you and the scene or community you’re writing about can decipher it, because they have the key to knowing who is being referenced. Chris Kraus has some very interesting critiques of what she thinks of as a kind of disingenuous fictionalization, which I talk about in my book. But some see that as an answer to the ethics of writing about others from real life.

To use a more Hollywood example: just this morning I was listening to Marc Maron’s podcast with Danny Trejo, who just published a memoir. And Marc asked, “Did you ask your family, do they know you’re writing about them?” Because Trejo is disclosing all sorts of things about his son—who has struggled with addiction—and his ex-wives and daughters. And Danny’s like, “Nope.” I had the sense that for him, and maybe a lot of memoirists or more pop cultural people who are not coming from a literary humanities context of thinking about these things, it’s just like, “This is a story I need to tell. And these are people who are a part of it. They’re going to be implicated and, and hopefully, that’s okay. I’ll talk to my lawyer about it.” And it seems like, for him and his family, it was okay. With autotheoretical work, writers like Nelson, or Bechdel in Are You My Mother? engage these issues on the page. And yet, as I discuss, both Nelson and Bechdel largely come to the same decision that Trejo does.

In contrast, Carmen Maria Machado in her In The Dreamhouse uses fictionalization and an iterative approach to telling a story through repetition, repetition, repetition (the repetition of trauma) to write through her experience of queer domestic abuse; even if there are people in her and her partner’s life who know the identity of the ex, Machado isn’t disclosing that ex’s name in the book. There’s some “protection” there—whether that is for the ex, or for Machado’s own legalistic protection. Pola Oloixarac’s Mona (2019) takes an autofictional approach too, to different effect. We get the sense that the protagonist Mona, a femme-y woman of color from South America who has received a tenured position in a creative writing program in California and who experiences being tokenized and institutionally instrumentalized for her WOC positioning, is in fact based on, if not at the very least heavily inspired by, her experience as an Argentine writer and translator who has lived and worked in San Francisco.

RB: I was excited to read about Killjoy’s Kastle: A Lesbian Feminist Haunted House, because it’s something I attended as a high schooler in Los Angeles. I went with a friend, and she remembered recently that she didn’t tell her parents the lesbian part, she just said that we were going to a feminist haunted house—perhaps a more traditional, internalized homophobia sort of “lesbian death.”

You introduce this concept of “lesbian death” alongside Killjoy Kastle’s Alyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue’s inquiries into whether or not “lesbian” is becoming discursively dead in the contemporary queer context. You ask, “Is there an endpoint to autotheory? A half life?” Can you expand on what you meant by that?

LF: I was thinking about this issue in relation to autotheory, discourse, fashionability, and trend. There’s so much smugness around language these days, without always considering the history or context of a given word. There are Indigenous people in my life who self-identify as Aboriginal or as Native or as First Nations; there are Indigenous-run institutions like imagineNATIVE, the artist-run centre and film festival, which I understand affirms the word “Native” and its histories. It’s the non-Indigenous people who seem to be the loudest in policing such language of Indigeneity and decoloniality. What of the Aboriginal person who for their whole life self-identifies with that term along with the specific reference to their community (for example, Swampy Cree), and who rejects the currently chosen-by-globalized-institutions-of-power (universities, presses, museums) term of “Indigenous”? Am I, as a white person, going to say: “no, we use Indigenous now”?! I can’t imagine anything more patronizing.

Something I continued to come up against during my PhD defense was: is autotheory “just” a trend? I was asked this many times. I don’t think it is. Sure there is a trendiness to it, but I really want to resist it becoming a trend. (I’ve taken a similar approach when autotheoretically writing about sourdough bread in the pandemic moment.) It was important for me that the cover of my book be the work by the Iranian conceptual artist Sona Safaei-Sooreh. It gestures at that ambivalence around commodification and capital in relation to autotheories and transnational feminisms and the way value circulates—both cultural capital and financial capital, in the case of US economic sanctions on Iran. As a Marxist-leaning person, I am interested in the politics of trendiness and the treadmill of the next new thing—this is a capitalist way of thinking. The idea of disposing what came before for the new, shiny thing. Where does this happen more than in academia? The treadmill of peer-review publishing? We each need to find our angle, publish our critique, say our new thing, which supplants the old thing, and the treadmill keeps on…

There are risks we run in throwing the baby out with the bathwater. That was what was happening, largely because of TERFs. The idea was that trans-exclusionary lesbians, who in my experience do tend to be a niche minority (thank god!), would threaten the futurity of lesbian as a term. But lesbian appears to be alive and well, now. It survived, and expanded, to become more actively inclusive. So that’s heartening!

RB: I’m on “lesbian TikTok,” where there is a lot of debate about the definition of lesbian, and how trans men or nonbinary people fit in. I’m always reminded of a Judith Butler quote on the signification of lesbian: “I would like to have it permanently unclear what precisely that sign signifies.”

LF: I have trans-masc people in my life who still identify as lesbian in the context of their relationships. They’re able to hold space for more than one idea. I think that’s actually what a lot of autotheoretical work and a lot of good autotheoretical work can do. Life so often happens in places of tension.

And yet, there is space for a fluidity of language, too. This is where my ongoing interest in fermentation comes in: fermentation, the biochemical process of microbial transformation, embodies preservation and transformation simultaneously. That is what first drew me to thinking about fermentation in relation to feminisms, in my ongoing project Fermenting Feminism and its offshoots like Critical Booch. What do we take with us and preserve, moving forward? What do we transform, leave behind, change? We leave behind feminisms that are trans-exclusionary or cis-centric, feminisms that center whiteness, to transform feminisms into more thoroughly intersectional, anti-racist, and decolonial modes. That is the aim.

RB: Autotheory appears uniquely situated for holding ambivalence; you quote poet Danielle LaFrance that satisfaction is “for eating ice cream.” What is it about the form that allows for contradiction and nuance?

LF: I think it is partly to do with the essay as a form. For a lot of writers working autotheoretically, there is an essayistic thrust in their writing, even if they’re working in forms like “nonfiction novels”. I think that’s partly what allows for a writer to move between so many different ideas and registers at once and yet still feeling like there’s a through line. The essay, from its earliest starting points as I understand it with [Michel de] Montaigne in the 16th century, is personal and confessional as well as philosophical, and can take a “braided” form. And so, is the whole history of the essay an autotheoretical one, too?

[The French word] essayer means to try, it’s always an attempt, an earnest attempt, a striving in the active and embodied process of thinking. Within the essay, writers can shuttle between different registers, topics, ideas. The essay as a form can hold a lot and still be a coherent thing; this is the power of collections of essays, or even books that move more nebulously between essays and storytelling and exegesis. Often, I’ve found, forms like art writing and criticism come into these autotheoretical essayistic forms too.

I also think that autotheory is itself a contradictory term, at least when one looks at a longer history of the development of “theory” in a Western tradition and its resistance to a clearly reflexive “self,” which I take up in my book when I consider the politics of “narcissism” via psychoanalytic theory, for example.

Do you have thoughts on if there’s something formally about autotheory that allows for contradiction?

RB: I think the stream of consciousness form that many autotheoretical works turn to helps illustrate a moving process of thought over time, instead of just offering one statement or conviction. It lays out a thought process, not just a thought. Autotheory feels less temporally fixed to me.

LF: That stream of consciousness can be endless. Maybe citations and grounding yourself in the context of thinking and research helps it stay both open and tethered.

RB: I want to ask about your section on disclosure and exposure. You see Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick as foreshadowing #MeToo, particularly with the strategy of naming. In Katherine Angel’s book Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again, she argues that those who share stories about trauma are doubly shamed — for the bad thing happening in the first place, and then again for disclosing what happened with the public. Do you think autotheory processes those stories in a different way than other forms?

LF: I’ve been thinking about Angel’s book as well as Amia Srinivasan’s The Right to Sex: Feminism in the Twenty-First Century (2021), which takes up similar ideas on consent, sex, desire, entitlement, and so on, as tied to present-day discourses of “freedom” and “rights” (in Srinivasan’s case). Their arguments are complicated, and I have to spend more time with those books before I have an intelligent opinion.

I do think autotheory has a potential to process trauma differently. In contrast to a memoir, where you’re relaying an encounter of sexual violence or trauma in detail for a certain readerly experience/gaze, with autotheory you might also bring in the “critical distance” of self-reflection, research, dialogue, and taking time with the material as part of a larger context of thinking. You are reflecting on the trauma not just to describe the trauma and relay it—this is the thing that happened—but to then move forward in mobilizing it, in a certain sense, to theorize something about trauma, violence, livability, justice, and so on. Enough time has passed, maybe, for you to be able to deal with the material in a way that is safe for you.

This brings me to a point I want to make about the idea of vicarious trauma, which I first learned about from Vikki Reynolds, a social worker based in Vancouver with whom I trained when I worked as a frontline community mental health and addictions worker (2010-12). The place I worked at was a drop-in with people who have concurrent disorders, which is the coexistence of mental health issues and addiction or substance abuse. Oftentimes, these were people carrying a lot of trauma with them and moving through the world with those wounds open. Vicky was aware that as staff, we were spending most of our days talking to people about their lives, and hearing stories in this casual, storytelling way. We sit and listen to traumatic stories. Those stories might trigger our own traumatic memories. What happens, energetically and psychically and socially, when you stew in a place of trauma sharing, letting trauma wash over you?

Vicarious trauma is a theory that says: if a person is relaying a traumatic story, not only are they risking re-traumatizing themself by reliving it, they’re also risking traumatizing the person who is “receiving” it, particularly if they aren’t ready to hear it and contextualize it (meaning, likely, if they aren’t a trained professional like a psychotherapist who understands how to work with trauma in a productive way). Like non-violent crisis intervention and bystander training, I see vicarious trauma as an approach that could be potentially very useful in non-social-work contexts, like in universities and literary and art spaces, where trauma is bound to come up. Especially, as you might know, in feminist spaces where you are taking up issues related to sexual violence, colonial violence, racist or racially-targeted violence, and so on.

I think about vicarious trauma in the context of reading, for example. People have different tolerances for trauma. I personally have a low tolerance for reading about any type of violence. I think it’s actually pathological, how physically empathetic (“highly-sensitive person”) I am: I literally will be close to vomiting if I read about violence, or see anything violent on TV, or see the sight of blood, and so on. This changes how I am able to engage with certain materials, and what I can even cover, as a scholar. That is something I’ve had to accept: I won’t be able to write about certain texts. It’s also a form of privilege, too—that I’m living in a context where I’m not exposed to certain forms of violence. In recent years we’ve come to language like “content warnings,” which might be useful, though also limited.

With the idea of being doubly traumatized, there’s also the risk of being doubly shamed. Especially for Two Spirit, trans, women, and nonbinary survivors, and survivors of color—it is a risk that you will become publicly shamed or blamed when disclosing your experience of being raped, for example. This, on top of not getting the justice you deserve as a survivor—because, as we know, the justice system is not designed for handling in a just way cases of sexual assault, rape, and harassment.

Autotheory as a form might “legitimate” (and I use heavy scare quotes here) lived experience, and make it seem more valid or serious or rigorous to those who would doubt the legitimacy of lived experience as a form of truth and knowledge and evidence, too. I think that’s why a lot of writers have in recent years shifted away from describing their work in genres like manifesto or confession to “theory.” We see that with Johanna Hedva’s “Sick Woman Theory,” which I talk about in the book, or Virginie Despentes’ King Kong Theory, or Cauleen Smith’s Human_3.0 Reading List, which I also discuss, texts that are arguably manifestos or essays, but are also doing the work of theorization and activistic catalyzing—in the case of de-criminalizing sex work (Despentes) or equipping Black communities with Black theory and critical thought outside of the bounds of grad school (Smith). These texts, all named by their authors as a theory — it’s intellectual, it’s critical, it’s going to be taken seriously by readers in a different way.

RB: You trace a generational shift between gen-x’s anti-ethical milieu and millennials, who are at least superficially ethics-conscious. Gen-z appears to have a unique blend of sincere politics and contrarianism or edgelording. Do you sense another generational shift in our contemporary moment? Is something brewing?

LF: I do feel like we’re reaching a peak performativity. Everyone’s performing for the camera, YouTube and TikTok influencers, it’s all about performing the self, and doing so within the bounds of certain capitalistic imperatives and branding measures. It’s the water within which we’re all swimming. And right now it’s about performing the self in an ethical way.

I am very interested in the idea of sincerity as it relates to authenticity and honesty in autotheoretical work. It was around 2015 when the idea of the “meta-modern” or “the New Sincerity” emerged for a moment as an offer of what might come after postmodernism. I’m curious about what “the New Sincerity” might mean. A literary nonfiction of the New Sincerity. Could that be the next movement?

Virtue signaling assumes that the virtue being “signaled” isn’t sincere—that there isn’t any true underlying virtue beneath the presumably disingenuous performance of it. So, then, the question becomes whether the current generation has a hyper-consciousness of ethics in the sense of truly living more ethically with others and being aware of the consequences of our actions, or if it is about being seen as ethical as part of one’s style or brand. The most cynical way of understanding this is that people perform virtue in order to achieve self-preservation, professional advancement, and so on. That happens, for sure. But I’m not so cynical. I do think there are people who want to act for the better good of humanity. Maybe?

My favorite TikTok artist is Nick Cho @yourkoreandad. I see that as an example of sincerity at work. He is performing for the camera, and there’s some humor and play, and yet he is sincerely and actually also being present as “your Korean dad” in a sense: a father figure present for those who need it. It’s performance, yes, but it’s sincere in its effects. He provides you with company. Your vicarious dad.

RB: I’m definitely down with sincerity. I feel like edgelording can sometimes be a manifestation of privilege, a way of maintaining distance.

LF: It does feel like it’s about distance, you’re right. It’s a way of keeping oneself safe. I see cynicism and irony as being productive sometimes, but if people are constantly hiding behind a shield of irony—how can any of us connect? And how could we connect across difference?

I wonder if the attitude of mine around sincerity comes from the context in which I was raised. I grew up in a very religious, low-income/blue collar home, in a diverse, working-class community, in a family and a larger community who had not attended college or university. Our neighbors and friends and family members were janitors and other such jobs. I wasn’t raised by coolly ironic, detached, well-adjusted(?) intellectuals like a lot of my friends were, and so I know my worldview is just fundamentally different.

This doesn’t make it easy for me to move through academia and its structures, language, and ideologies. Many times I want to leave for something that feels more honest or relevant to life. Maybe this is partly what has brought me to an interest in whatever autotheory is. I feel very nourished and excited by the work emerging by other first-generation students and scholars, many of whom are Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other People of Color (or, as has been offered, People of the Global Majority). My next book is on autotheory in the 21st-century with a focus on the lens(es) of first-generation student experiences. I hope to find ways of dialoguing with others and incorporating conversations as part of a larger theorizing of issues like intergenerational class mobility, labor and knowledge, and the future of the university.

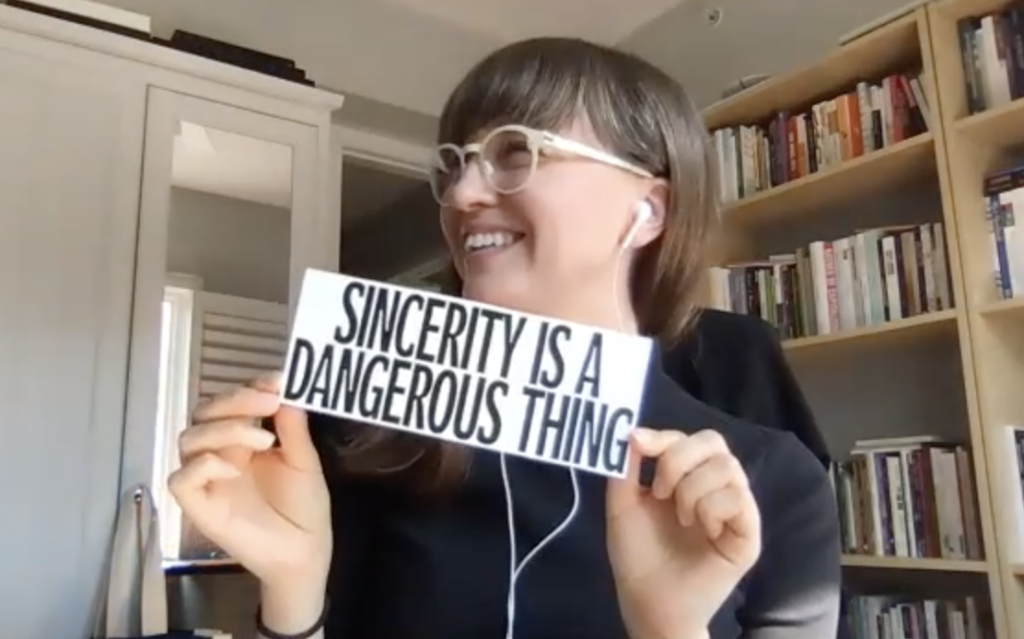

I’ll show you a magnet I made from a magazine collage when I was nineteen years old. It’s hung on the fridge of the many apartments and houses I’ve lived in, and now hangs on my magnet board in the room where I work. “Sincerity is a Dangerous Thing.” That you might perform yourself in a way that is aligned with who you feel you really are, and the ethics and values that you honestly hold, even if the “true personal” is fictionalized or withheld from the public view. I’m one of the few, perhaps foolish, academics who believes it is possible to be sincere, or at least attempt to be, even as I understand that every written or oral enunciation is a rhetorical construction, a performance of sorts, and even as I feel the very notion of “sincerity” slipping through my fingers as soon as I try to grasp it.

RB: What are you working on, now?

LF: I’ve been writing more fiction lately. I recently published an autofictional short story “The Grateful Dad” in Soft Punk Magazine. It’s a reflection on class, colonialism, and collectibles in a blue-collar neighborhood in the prairies on the eve of Y2K. The story is part of a larger collection of stories I’m working on, that engages with my childhood experiences growing up as a white, working-class settler in Saskatchewan in the 1990s. It’s all autofiction. I’m also starting to write the next autotheory book, as there is so much I want to say that I didn’t get to say in the first book! I have a chapter on early Metis and Indigenous women’s memoirs as autotheory forthcoming in an edited collection. I continue to do quite a bit of art writing. Most recently, I wrote a catalogue essay for the artist Ayla Dmyterko’s exhibition in Glasgow. It’s called “Post Peasant Protest.” Her and I reflected on our shared Ukrainian settler backgrounds and the funny coincidence that we both grew up in the exact same neighborhood in Regina. She had engaged deeply with my book in the lead up to her show, which I found humbling. The process of writing about her work was an active exchange between us: I like that form of writing best.

Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism is available for purchase through MIT Press. More information about Lauren Fournier and her work is available at www.laurenfournier.com.