Reviewed by Grace Novarr

It feels almost unfair to review the first novel by Marguerite Duras (1914-1996), whose literary prowess has been proven by her body of work, spanning her entire lifetime. Including works such as The Sea Wall in 1950 and The Lover in 1984, Duras produced dozens of novels, plays, and screenplays. Duras was an icon of the nouveau roman, a French literary movement that prioritized experimentation over plot and characters and included figures such as Alain Robbe-Grillet. She is perhaps most known for writing the screenplay of Hiroshima mon amour (1959), one of the most celebrated films of the French New Wave, directed by Alain Resnais.

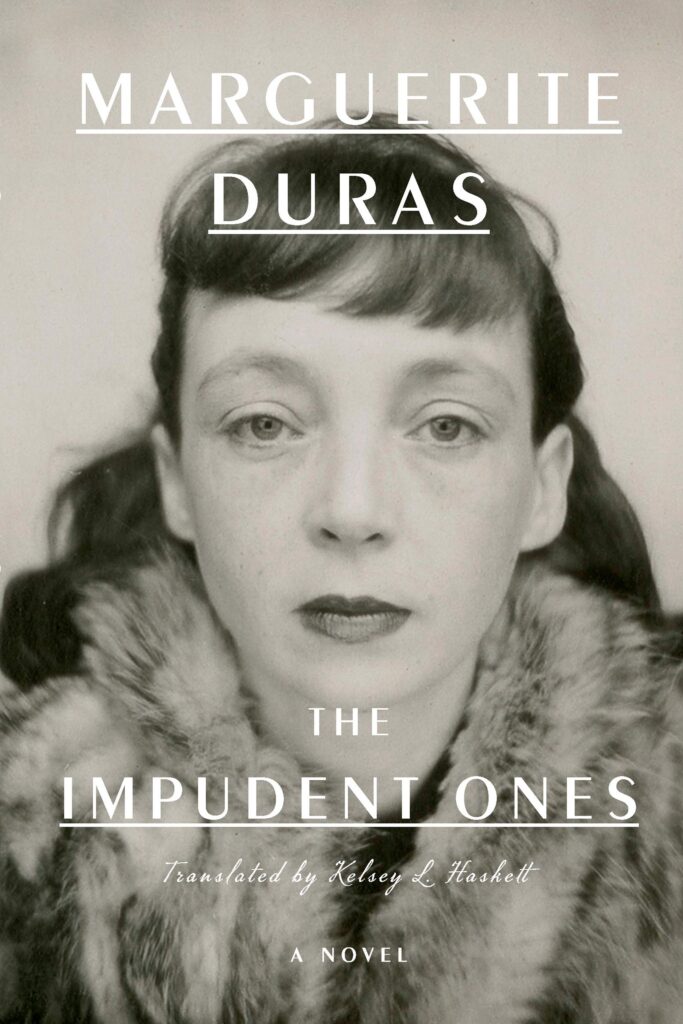

Over the course of her successful career, Duras saw fit to disclaim The Impudent Ones, her first work. In an article in the New York Review of Books, author Edmund White quotes her as admitting that it was only published due to professional connections she formed during World War II when she worked as a state censor for a publisher under the Nazi-occupied government: “If my first novel finally appeared…it was because I was part of a paper commission (it was during the war). It was bad….” Nevertheless, in 2021, The Impudent Ones was translated into English for the first time by Kelsey L. Haskett, exposing it to an anglophone audience that would previously have had no way to read it when making their way through her oeuvre. Hailed as “a major publishing event,” the release of the 2021 edition certainly marks an exciting moment for anyone interested in Duras.

All the promotional material for the text, including the afterwords included in the 2021 edition, focuses on the inherent intrigue of the book as the obscure first novel of a major writer. Unfortunately, that factor proves to be the most significant thing about it. As an admirer of some of Duras’ later work, especially the fascinating The Ravishing of Lol Stein, I was certainly able to identify in The Impudent Ones some germs of Duras’ later achievements, but in my efforts to understand the novel on its own terms, as if it were not necessarily the precursor to a great literary career, I was left disappointed and frustrated by the experience of reading it. As opposed to later works like Ravishing, in which Duras broke down sentences into essential units of meaning, Impudent Ones was more traditional and less engaging.

When reading literary fiction, an engaging plot is more an asset than a requisite. The reader, heading into a book by a celebrated sculptor of language, expects writing that dominates the page, providing pleasure or at least insight. The plot is merely a vehicle, a moving backdrop against which the talents of the author are meant to stand out. However, when the writing is discovered to be less than dazzling, the reader’s attention turns to the plot; they search for something to maintain their engagement with the work, asking simply for a reason to care about the unfolding of events. The most disappointing experience, however, is when a story that should be interesting and emotionally affecting is made cold and flat by the writing itself. Such was my experience of reading The Impudent Ones, which buried an intriguing premise under confusing and inconsistent writing.

The Impudent Ones is fundamentally a traditional realist novel about social and family dynamics, although Duras’ experimental style, which would be developed much more strongly later on, makes categorizations of genre difficult. Originally published in 1943, the novel portrays the dysfunctional Grant-Taneran family, headed by the failing matriarch Marie Grant-Taneran, whose eldest son, forty-year-old Jacques, is almost cartoonishly immature and selfish. The novel opens as he mourns the accidental death of his wife of one year, though it becomes apparent that his sorrow is really more connected to his financial struggles, which drive him to ask for money from every single one of his family members. The book largely adopts the perspective of Maud Grant, the twenty-year-old daughter, who is rejected by her family members yet feels impossibly connected to them. There is another sibling, the teenage Henry Taneran, whose presence does not contribute to the plot in any way; he is a ghostly apparition circling the novel, one of many details with which Duras plays with the traditions of realistic fiction by including characters and scenes that promise to be important but lack tangible significance. The Grant-Tanerans spend a season in Uderan, their previously abandoned estate in the southwest of France. There, they encounter John Pecresse and George Durieux; Maud’s family wants her to marry the former, but she begins an affair with the latter.

Despite a few significant plot developments, including suicide and scandal, The Impudent Ones is willfully stagnant. Duras’ portrayal of a family trapped in a cycle of abusive enabling and withholding of affection rings true in the first few chapters as the family is introduced, and their dynamic fleshed out. And yet, as the book progresses and the dynamic does not evolve––toxic mistrust and hostile motives rule the family’s life ––the story grows more life-like and more dull.

When the novel ends with the family situation largely as it stood at the beginning––with the exception of Maud’s escape to live with her lover––one simultaneously wants to give Duras credit for accurately capturing the hopeless repetition of deluded dysfunction, and censure her for revealing the entirety of the family’s situation at the beginning of the novel, allowing no room for the characters to develop. The reader’s expectations eventually adjust to the reality of the novel’s hopelessness.

Throughout the novel, there are occasional sentences that summarize entire thematic facets of the text. In Chapter 3, Duras describes “the strong pull of the family circle, where nothing, not even idleness, could lessen the interest they had for one another,” a characterization that is accurately borne out by the novel and in a way functions as the thesis of how all the relationships fluctuate. In Chapter 7, Duras details the pattern of behavior that occurs when a new person begins to interact with the Grant-Taneran family and is caught in the middle of the family dysfunction: “It was then up to him to make the effort to adjust once again to the rhythm, ultimately monotonous, of this kind of perpetual movement of discord and heartrending emotion. Most of the time, he got tired of it.” Again, this sentence is striking with its psychological accuracy, but therein lies the problem: Duras is so eager to portray the “ultimate monotony” of family discord that she replicates it for the reader.

This might not be such an issue if the Grant-Tanerans’ specific family situation wasn’t rendered so halfheartedly. In the following paragraph, Duras writes of Maud’s burgeoning lover George: “Though he seemed to be losing interest in Maud, he quite often stopped at the domain anyway.” She often employs the storytelling strategy shown here of jumping past developments in characters’ emotions without an explanation, perhaps to make the point that these emotional developments are inevitable given the cyclical family dynamic. Yet without access to the characters’ inner lives, the reader is shut out of the emotional drama. Novels about monotony and the toxic cycle of (inter)personal dysfunction always risk losing the reader’s attention, but the best works in this category sidestep this issue by introducing suspense and raising the stakes with the possibility for change. By announcing outright that the Grant-Taneran family won’t be changing its ways anytime soon, Duras renders the remainder of the novel flat and hopeless.

Duras’ writing is characteristically opaque, which evidently presented a difficulty for the translator. Haskett notes that “the problems of lucidity and cohesiveness, first recognized by the two French presses that dealt with the novel, still present a challenge to the reader and the translator today.” To address these problems and render the text comprehensible, Haskett adopted a strategy of “the addition of occasional words and phrases, not in the original, to provide smoother transitions as the text unfolds.” While this strategy was no doubt necessary, its effectiveness is questionable, as there were many moments in the text where phrasings were either unclear or awkward, two faults that could belong either to the author or to the translator. For example, strangely phrased sentences like “Even if Henry led a degenerate life, he inspired confidence and was likable” stopped me in my tracks as I read.

Specific instances of word choice stood out, such as when a character is described as “masticating his food.” This is a direct translation of the word in the original text, mastiquait, which in French has connotations of chewing for a long time without swallowing, but in English stands out as an unconventional word choice that contrasts with the comparatively mundane language of the surrounding paragraph. Similarly, Jacques describes how his dead wife’s body was brought to him by “the chums who were with her.” While “chums” is an accurate translation of copains, it nevertheless strikes the reader as discordant with the rest of the sentence in English. Additionally, there were several moments of clichéd language, such as “He couldn’t believe his ears,” which were direct translations of the original French but nevertheless stood out from the more dreamlike and distant tone of the rest of the surrounding paragraph. Instances in which contractions like “didn’t” and “couldn’t” appeared were jarring, considering the overall detached formality of the text and the fact that such contractions don’t exist in the original French. Overall, the translator seemed to privilege a line-by-line accuracy that only undermined the “lucidity and cohesiveness” that she ironically claimed to prioritize.

In the 2021 edition, the contextualizing translator’s note appears not as a foreword but as an afterword; thus, context for the novel is provided not to enhance the reading experience, but to enhance the more complex and hazy experience of digesting the whole of the novel’s contents. Haskett’s afterword explains that a critical reevaluation of Duras’ oeuvre has restored The Impudent Ones to its rightful place as the progenitor of an impressive lineage of semi-autobiographical writing. Several pages of the translator’s afterword are devoted to explaining all the plot elements of The Impudent Ones that are echoed in Duras’ later novels: the fickle and dominating mother; the selfish and cruel older brother. Following the translator’s note, there appears the essay “The Story Behind The Impudent Ones,” penned by Jean Vallier, which provides biographical and historical details of Marguerite Duras’ life that serve to make it clear that the novel is tantamount to a heightened autobiography, and that Duras’ family history is one that she told and retold throughout her career as a writer. These essays show that “Impudent” is no more than a shadow of Duras’ later and greater achievements: they were probably placed at the end so as not to discourage the reader from undertaking this ultimately tedious novel.

Certainly, Duras is not for everyone. And yet the traits that inhibit The Impudent Ones–repetition, opaque writing, unlikable and impenetrable characters–are all hallmarks of her later and more successful works. Perhaps the most useful function of Duras’ debut is as a testament to the possibility of an author’s development. Rather than turn away from the aspects of her first novel that make it difficult to fully enter into, Duras leaned into them much more fully in her later works.

What mars her first novel, then, is not a lack of talent but a lack of commitment. The Impudent Ones stands on the boundary between a traditional novel and something more experimental and artistically significant. Once Duras let go of the constraints of the realist novel, her fiction became much more interesting and important, even as it became more obscure. As it is, her first novel sways on the tightrope of tradition, but each time it leans over the edge, it stabilizes again. One gets the sense that Duras should allow herself to plunge, which, indeed, she did. Perhaps, as the translator’s note implies, she needed at all costs to tell her family story, and the first manifestation of this need took the form of a difficult and vague artistic effort. But as her career developed, she found the right form and style to make her story affecting.

Across The Impudent Ones, there were certainly moments of beauty that the translation captured, including specific turns of phrase and psychological descriptions that foreshadow Duras’ talent for depicting harsh mental realities. When Maud returns to her family after having fled to be with her lover, Duras writes: “She wanted to flee from them, above all, to avoid the repulsive intimacy to which she would still be summoned, no doubt, once their anger had passed.” It is this “repulsive intimacy” that Duras excels at depicting ––it is the strongest aspect of this novel and a hallmark of her later works. However, such moments were sparse in the context of a text that felt, for the most part, superfluous and overwritten. While The Impudent Ones, as the afterword makes clear, has a lot to offer for the reader who’s a serious Duras fan and wants to chart the beginnings of her literary career, anyone simply searching for a compelling read should stick to her later and more accomplished works.