Our editors review the art they loved this year. Cover photo by Em Sieler.

Poetics of Work by Noémi Lefebvre (translated by Sophie Lewis)

Reviewed by Ezequiel González

“Il règne en ce moment quelque durcissement qui influe vraiment sur tout le monde.”

“Some kind of fog has descended which is enveloping everybody.”

In the good city of Lyon, a state of emergency suffuses the everyday movements of its citizens. Like a fog slowly rising up on a stage, Sophie Lewis’ recent translation of Noémi Lefebvre’s Poetics of Work envelops the reader in a breathless exposition aimed at the heart of rising nationalism, growing fascism, and quotidian State violence(s). Lefebvre’s gender-neutral narrator—an unemployed poet—wanders unmoored through a quiet occupation, reflecting on the absurdities and contradictions of the modern surveillance state. This vaguely warlike setting gives the narration a theatrical accent as our poet zooms in and out of Lyon within the same breath, remarking repeatedly that all is nothing more than a farce. Throughout, the poet’s father offers a Kantian, pseudo-intellectual antagonism. Mimicking the omnipresent State, he cycles in and out of the storytelling, offering rebate sophistry through “impartial” patriarchal impositions. Our detached narrator psychoanalyzes these interactions and the overarching national fog in a sort of canalized stream of consciousness, wandering about, yet startlingly immobile and inactive: crushed under an existential weight that perhaps characterizes our times.

Sophie Lewis’ translation is at once expansive and incredibly precise. Lefebvre’s language is rarely declarative, instead soaked through with deep cultural and linguistic metaphors, furthered by witticisms that no doubt reflect the poetic impulses of the narrator. Nonetheless, Lewis’ translation renders this language seamless and light. Readers can remark how, even in English, there is a distinct flow and ear for consonance. Presented without context, this translation could even be passed off as an original work in English. In a sense, Lewis mimics Lefebvre’s zooming motion: allowing the precision of the local to remain intact while granting more freedom of movement to the larger flights of language. In this way, despite the detached narration, Lewis’ treatment of Lefebvre feels quite intimate and refreshing, especially as the momentum of fascism and police brutality continues to run rampant in the United States. Despite being written in 2018, Poetics of Work feels particularly responsive to the Black Lives Matter and anti-fascist mobilizations of the summer of 2020, pointing to Lewis’ care as a translator both conceptually and at the level of the word.

While Poetics of Work provides a detached panoramic of consumerism, globalized capitalism, spectacle, and surveillance, Lewis’ translation expands this bird’s-eye view beyond the original limits of the novel. English-language readers can surely sense a transnational kinship with Lefebvre’s incisive reading of protest and surveillance, due in no small part to Lewis’ supple and delicate craftsmanship at various levels of translation. Sophie Lewis’ new translation of Poetics of Work is certainly an exciting literary prospect for American audiences, especially within the current sociopolitical fog of the receding Trump era. Lefebvre’s narration of a detached and inactive “actor within the system” of spectacular capitalism offers a salient counter-narrative to the Instagram-infused discourse of “ally fatigue”; pointing instead to omnipresent systems that engulf society as a whole. As such, Sophie Lewis’ introduction of this work into the English language is a welcome and exciting resource for a global society resisting a myriad of invisible hands, nationalisms, and political obfuscation.

The Weak Spot by Lucie Elven

Reviewed by Ezequiel González

“It seemed that I might be walking around in a long pause, an ellipsis…”

A young woman takes an apprenticeship in a small pharmacy nestled in an unspecified European mountain village. Patients circulate in and out, trafficking in stories and secrets, threading the unnamed apprentice into complex entanglements with the locals; all under the watchful eyes and ears of the head pharmacist, August Malone. In a curving yet extremely economical style, Lucie Elven’s debut novel The Weak Spot spins a colorful, controlled narrative of longing, power, and selfhood within and outside the body. In a steep prose, the young apprentice narrates the stories gleaned from across the counter, layers of shrouding obscuring the motives of all parties and contributing to an overall sense of incomplete emotional gestures. Further, the apprentice’s descriptions of Mr. Malone, a male shadow pulling strings at the edges of our vision, deftly undergirds the work almost unconsciously throughout. Yet as the novel progresses, the narrator’s voice noticeably transforms, her pacing and tone altered by the surrounding dramas of the town and the constant surveilling presence of Mr. Malone. Despite the first-person present structure, the narrator’s ego begins to drip and melt at the edges: a psychoanalytic exercise that renders the writing impulsive, suggestible, and a part of the fictive circulation that is the lifeblood of this town.

Elven’s precise control at the level of the sentence is apparent wherever one looks. Rarely is there a superfluous word or action within this narration, highlighting both the internal locus of control that is the main narrator as well as the power structures that surround her. While this novel’s indirectness does give it a meandering contour at times, the implicit propulsion of these quiet power relations gives readers a sense of direction and structure throughout. We can identify the effect of wandering through a fog-like memory, approaching the limits of a dream yet suspended; grounded, not fully released into absurdity. In this way, The Weak Spot is a strong first debut by Lucie Elven, clearly demonstrating her poignant yet subtle style, and providing an exciting look at an emerging contemporary writer one should keep on their radar.

The Hard Crowd by Rachel Kushner

Reviewed by Campbell Campbell

I wish that I could sit with my favorite writers and hear their thoughts on everything from politics to the emerging literature of our time, and I wish that I could remove the stigma of authorial intention and undo the death of the author just for a night. With The Hard Crowd, I can do just that with Rachel Kushner.

Kushner has written three well-researched and ambitious novels and has been private about her personal life for most of her career, but she sits down and tells us her thoughts on topics ranging from Jeff Koons, Denis Johnson, Marguerite Duras, to the Italian leftist movement. While The Hard Crowd functions as cultural criticism, literary analysis, journalism on artistic movements and international fiction that she encountered in her adult development, I couldn’t stop reading when I began to think of it as the new memoir mode.

Kushner knows that the line between fiction and journalism have blurred over the past twenty years and that she cannot give a journalistic account without inserting her creative license and voice, so she decides to embrace a personal address and include herself in her journalistic essays. Kushner examines her encounters with a Palestinian refugee camp, an illegal motorcycle race, the 1970’s drug scene, in addition to the Western novels and Brazilian fiction that have shaped her consciousness and literary successes The Mars Room and The Flamethrowers. The reader is caught in this new memoir mode: they are able to watch her intellectual and political development over the span of twenty years as she discusses her thoughts on these subjects. And the reader witnesses her growth as she becomes a prison abolitionist as well as the almost champion of a cross country motorcycle race.

While The Hard Crowd will surprise you with its clear argumentative voice and its critical understanding of cultural movements, you will be most surprised by Kushner’s capacity to love and understand so many communities of which she is not a direct member. She does not merely make stories of her subjects; she participates and loves and grieves the characters that have shaped her to be the woman she is today.

The Second Place by Rachel Cusk

Reviewed by Campbell Campbell

Do I need to be acknowledged by another person to be a full self? Do I let myself become the mirror of another person’s desires? How do I make myself invisible in order to not be criticized?

In her new novel Second Place, Rachel Cusk asks the questions that I have been afraid to utter all of my life. For the unnamed narrator, a female writer and mother like Cusk herself, these questions are no mere musings. She lives and loves and suffers through them in her adulthood.

Rachel Cusk has become famous for her dazzling auto-fiction Outline trilogy in which a woman travels to new locations and has a series of personal conversations with strangers in the span of a week. The Outline trilogy borrows from Virginia Woolf literary tradition with its long passages on the various characters’ interiorities and its de-emphasis on the first person narrator. The Second Place, however, disrupts this pattern entirely by being consumed in and limited to the thoughts and concerns of the main character. The plot toggles between melodramatic solipsism and bittersweet realism: the protagonist is a writer, mother, and woman in the middle of her adult life and in need of something that she struggles to articulate–artistic inspiration that one can only find in a friend. She invites her favorite painter to visit and be this source of inspiration, but she rather experiences emotional upheaval when he arrives and is not willing to acknowledge her. She believes that she needs his acknowledgement to be a full self and risks the rest of her life in this pursuit.

Second Place is psychologically perceptive and truly beautiful to read as the main character comes to new realizations about herself through long meditations. To read this book is to risk Freudian and Lacanian self-analysis. However, Cusk proves that this procedure needs to be undergone in order to flourish in your relationships and love yourself.

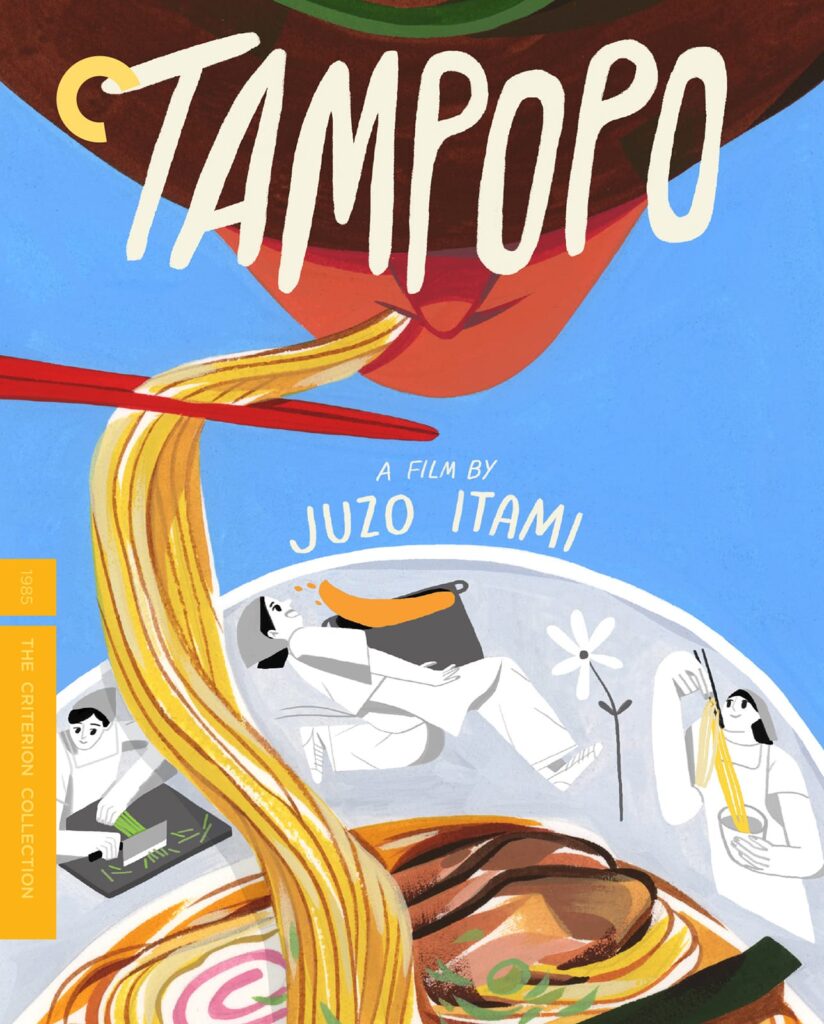

Tampopo (written and directed by Juzo Itami)

Reviewed by Annelie Hyatt

Tampopo (dir. Juzo Itami) is on the surface just an eccentric film that celebrates the Japanese art of ramen. The movie floats through a loosely connected series of stories that trace the efforts of the widowed restaurant owner Tampopo to rebuild her failing business into a first-class ramen shop. These efforts are spearheaded by the lone rider Goro, a truck driver who looks as if he’s ridden straight out of the Wild West. Together, and with the support of a surly, well-meaning gaggle of men, they transform Tampopo’s antiquated ramen shop into a Western dream, and a Japanese nightmare.

“We do not dislike everything that shines, but we do prefer a pensive luster to a shallow brilliance, a murky light that, whether in a stone or an artifact, bespeaks a sheen of antiquity,” writes Jun’ichirō Tanizaki in his famous essay In Praise of Shadows. In the beginning, Tampopo’s ramen shop is obscurely lit, illuminated only by the sunlight that filters down through the restaurant’s red cloth banner. It is enough. The counter is made of a rich, clouded oak.The kitchen utensils are clean but clearly worn, bearing the grime of time and labor and ramen made from somewhere deep in the hands. They are enough.

All of this is destroyed when Tampopo renovates her shop after perfecting her ramen recipe. The restaurant becomes a total, blinding white, boasting an outside banner that bears Tampopo’s name in gold cursive lettering. Nothing escapes illumination. The counters are a hard stainless steel, the counters a smooth, varnished wood. Tampopo stands tall in her white toque, coat, and apron. They could be in France. The men stroll in, accoutred in berets and ties and captain hats, and we remember, for the first time, that this is not a Japanese story but an American story as well. Just as Goro is dressed in the style of a cowboy from the “Wild Wild West,” so too does The West clothe each element of the film, each Japanese body.

“I grew up in a miserable family, so I wanted to make my own home the warmest there was,” Goro says, one night when he and Tampopo are nearly finished redesigning the restaurant. She is wearing a beret and brightly polka-dotted dress. “I got married. We had kids. And we had a warm home.” He looks at her for a moment, and then out the window again. “But I never felt comfortable there. I don’t know how to act in a happy home.”

This line resonates in my mind as I regard Goro’s stunned face, his mouth hanging open at seeing Tampopo’s renovated shop before he laughs and shakes the architect’s hand. It’s a moment of subtle, primal horror, before the initial reaction is conquered by the person he’s become, a man unable to truly free himself from the values of his time.

Regardless of the director’s intention, the reopening of Tampopo’s ramen shop seems a pyrrhic victory at best for the characters against the occidentalizing forces that gut them. This issue is especially relevant today, when Asian media forms such as anime and K-Pop are becoming more and more entangled with Western audiences, Western genres, and Western forms of recognition from the Oscars to the Grammys. Where success is associated with Western assimilation, ramen rots in the corner.