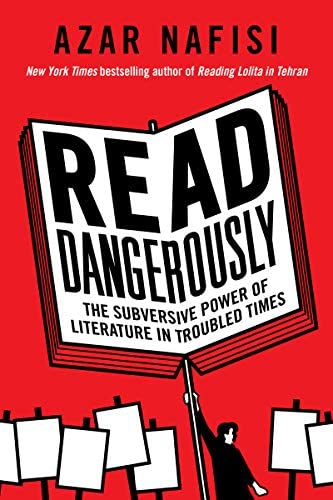

CJLC editors Tejal Pendekanti and Rea Rustagi interview Azar Nafisi on her recently published book, Read Dangerously: The Subversive Power of Literature in Troubled Times, which is structured as a series of letters written by the author to her late father. Diverging from a familiar form, the memoir, in this new book Nafisi contemplates how literature can challenge totalitarianism and illuminate an alternative path forward.

Nafisi’s other works include Reading Lolita in Tehran, The Republic of Imagination, and Things I’ve Been Silent About.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

February 28th, 2022. 2:30 p.m.

Tejal Pendekanti: Reading Lolita in Tehran is divided into four separate sections that correspond to an author and a central text. In Read Dangerously, you similarly center each letter around a specific text. Can you talk more about how you’ve selected the works for Read Dangerously? Can you also talk about how you use texts similarly or differently to how you used them in your first memoir?

Azar Nafisi: To tell you the truth, I read so many, dozens and dozens of books. Of course, it was partly an excuse for me to read and reread. It was fun. But I chose the books that I felt addressed one aspect of the main theme, which is this totalitarian mindset versus the democratic one. For example, with [Salman] Rushdie, I go back to the beginning of the conflict between the poet and those who are in power. This goes as far back as 2000 years ago—the Poet and the Philosopher King in Plato’s Republic didn’t get along well. But with Zora Neale Hurston and Toni Morrison, it is about racism and sexism and how you stand up to them. The third chapter of the book is about war, which is the most extreme way of polarization.

Then with [Margaret] Atwood, it is about living in a totalitarian society. And with [James] Baldwin….I really feel that Baldwin is so relevant to what is happening today. He fought against racism, and participated in The Civil Rights Movement, but at the same time, he didn’t allow hatred to overtake him. He never became the other side of the coin to the racists he fought against. So, I wanted to end it with him, as a model of how we might act today. That was how I chose the texts.

As for Read Dangerously being in the letter form, I didn’t want to write just literary essays. I was also living in a weird time that did not fit into that genre. I mean, there was the pandemic, and there was the former president, and a deeply polarized society. And I felt the need to speak about all this—there was an urgency. But at the same time, I did not want the book to be a political tract. I wanted to capture the mood of the time, going beyond politics while at the same time addressing it. I found myself writing letters to a series of people, past and present, from my father to Donald Trump, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Benjamin Lay, and James Baldwin. But these random letters were not a book. Then I tried writing to the authors of the books I was reading and rereading, but it became too artificial. I didn’t know these authors well. The letter is an intimate form, and I wasn’t going to write them to tell them what their books were all about. That would be crazy. To make a long story short, I was talking to a friend of mine, and I was telling her about my dilemma regarding whom to write the letters to and she said, why don’t you write to a third person. I thought, That’s a great idea. My father and I had such a long, long relationship. Over the years, we had written to one another, we had conversed with one another about a lot of these issues, and he just seemed naturally to be the person I should write to. And so that is how I chose to write him the letters.

TP: I noticed that in your last memoir, you focused on your experiences in Tehran, where you discussed the importance of fiction in totalitarian societies in the Republic of Imagination. How has Read Dangerously expanded on those ideas?

AN: Well, you know, Reading Lolita in Tehran was about how fiction opens spaces in a totalitarian society. Republic of Imagination was the story of how I became an American. Some people feel that when you love a country, you should constantly repeat, “Hooray, this is a great, great, great country!” Now, I feel that if you love a place, you care enough to worry and to say, “Why are things not going the way they should? We should change this, we should do that.” As soon as I felt that I wanted to become an American, I decided, I’m going to work on things that I’m not happy with.

That didn’t mean, though, that I wasn’t going to work with things that I was happy with. American fiction became the center of how I understood America. I think that there’s something about American fiction which is very interesting. Its central characters are often marginal, from Huckleberry Finn and Jim, to the protagonists in Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin or Carson McCullers and many others. These marginalized characters through fiction come to the center. I was very much taken by that. I felt that the best representation of America is the American novel. That is what I was doing with Republic of Imagination: writing about fiction that presented America, both at its best and at its worst. With Read Dangerously, I wanted to talk about the polarization that I had experienced in Iran in a totalitarian society that I was experiencing here in some segments of the country. How do we stand up to totalitarian trends and tendencies in a democratic society? How does fiction stand up to this polarization? These are some of the central questions of this book.

I believe that totalitarianism is a mindset and imagination is the mindset that stands up to it. Because fiction by nature is democratic. I mean, in a great work of fiction, every character has a voice; the writer has to go under the skin of all the characters. Good fiction is inherently diverse. In bad fiction, we have the author imposing his or her views on everybody else. The characters become the author’s puppets rather than live beings. Fiction stands up to the totalitarian mindset and becomes dangerous to it. That is why totalitarian mindsets, one of the first things they do is censor or ban or put authors in jail. We see censorship and the banning of books in this country right now as we speak.

Rea Rustagi: Discussing the content of Read Dangerously more specifically, one of the letters focuses on Toni Morrison’s book, The Bluest Eye. Books that have themes related to sexuality, rape, and racism are under assault, specifically in curricula for school-aged children. Specifically in these educational environments, how can we cultivate a culture where we’re more cognizant and able to resist that backward slide into censorship and book banning?

AN: We are living in very dangerous times. It’s a time of transition. On one hand, we see more diversity, more protests for justice. These are all good things that are happening, but then there are also bad things that are happening and censorship and banning books are part of that. One excuse for censorship in this country is the issue of morality. But there are books that are not about incest or rape or things like that, but they are deeply obscene and immoral because they are shallow, they remain on the surface, are preachy or sensational. Another excuse for censorship is that some books are too disturbing and painful, and we should protect our youth from disturbance and pain. Well, honestly, if you can’t tolerate pain in a work of fiction, how are you going to face up to pain in real life, and you cannot escape from life’s pain. So to ban it, to ban [depictions of] rape, you’re in fact protecting our youth from life, not from obscenity. That is why I think it is up to our youth today, to act maturely, because the so-called grown-ups are not acting maturely. Great fiction is always disturbing, it reminds us of life’s complexity and ambiguity, it depicts joy but also sorrow and despair. [James] Baldwin used to say that people hate so they can hide the pain. Because hating makes it easy. If you hate someone, you don’t have to think about them. You don’t have to see the complexities and the ambiguities. But imagination and thought are the exact opposite of that experience. Through imagination you put yourself in other people’s spaces in order to understand them and to not just judge but to understand the complexity and the contradictions and the paradoxes of being human. Even when you fight an enemy you need to understand them in order to win.

RR: One of my concerns about book banning is that when children aren’t taught or are exposed to certain things, they don’t know how to recognize them. When we talk about systematic racism, for example, it becomes easier to reject that it is a reality when you don’t believe that it exists in the first place.

AN: Yes, you are right. And one of the reasons for stories is that stories put us in places that we have not been before, did not know before. Children’s stories in fact have quite a bit of violence in them. They are filled with evil witches and poisoned apples, dark, disturbing and dangerous places. Take the brother and sister Hansel and Gretel for example: their father and step mother abandon them in the forest where they meet a witch who wants to fatten them to eat them. They have to use their wits and stand up to the problem and fight the evil witch in order to gain maturity. This is how the fictional experience prepares us for real experience.

TP: Similarly to our discussion on censorship, we were wondering, as an academic, what role do you think educational institutions, like universities and colleges, should play in either combating or advancing censorship of certain ideas? Simultaneously, as students, how can we work to resist censorship within systems that we already participate in?

AN: One of the most important things is to have a dialogue. We can’t just take sides because this is not about taking sides. It’s about understanding that censorship comes from a mindset that cannot tolerate others, that essentially centers around elimination and interrogation. You go to college in order to understand and gain knowledge, and college is the only place where you can talk about everything, where you should talk about everything; it is a free market of ideas. If we lose the ability to have a dialogue with those we disagree with, we are in danger of losing our freedom. The first thing that I suggest is that we should try to bring about the discussions about censorship to colleges, and through colleges back to our communities. The other thing is that we need to form subversive book groups in schools and on campuses where we study and discuss banned books.

RR: One of the letters in Read Dangerously focuses on Margaret Atwood and her novel The Handmaid’s Tale. In that letter, you discuss how the experience of living in an oppressive regime is very complex. What do we gain from understanding that the same people who are victimized in these oppressive regimes can also be implicated in their activities?

AN: That is a pillar of totalitarianism: when victims become complicit in the totalitarian system they pave the way for totalitarian regimes to take over and maintain power. That is why I am so worried about the United States. When I think of the elections and fights over voting rights, the hierarchical and totalitarian ways that segments of the country are acting, creating a leader who no one can question, lack of tolerance for those we disagree with—these are all warning signs. What happened in Atwood’s republic was that people were not paying attention to the signs. Sometimes they even went along with them. And then, one day they woke up and all their freedoms were gone. The protagonist says something like, “How did we know we were happy? We didn’t know.” That is the same as what happened to us inside Iran. We wanted more political freedoms. But when you want more, you have to make sure that what exists is not better than what will replace it. We just wanted the Shah to go, without thinking about who would replace him. What replaced his rule was this huge theocracy, like the one Atwood so well portrays in her book. Did you notice that in every totalitarian society the victims are always women, minorities, and culture? They are always the first targets.

RR: As you noted in your book, and as we saw in the Trump administration and are still seeing with the Biden administration, in the apparatus of neoliberalism women and minorities are still also instrumental to furthering the goals of a regime. We see how they can be incorporated into the system.

AN: That is why we need debate and discussion. The way things are right now, everyone is polarized; everyone has a core belief and they feel safe in that corner. What we need to do is take a risk and destroy these corners and meet more and speak up more. The future belongs to you, so you have to take ownership of it. One of the important things is not being incorporated into the system. It is becoming aware of the dangers of being incorporated. It is important that, once in power, you do not act the same way as the powerful ones you used to criticize.

RR: In your first memoir, Reading Lolita in Tehran, you focus on differentiating heroes from villains. It has been many years since that book was published. We have been having this conversation about self-recognition and totalitarianism—how has your conception of what constitutes a hero or a villain changed over time?

AN: Before I was writing Reading Lolita, I had so much anger in me, so much anger. Once I started writing–it is amazing, you don’t write because you know everything, you write because you don’t know many things and through writing you discover them. What I discovered was that these people whom I called villains in my real life, and who made life very hard for me, they had their weaknesses and they were complicated. So for example, if you look at Reading Lolita, many characters in that book were Muslim. But they come from very different spaces. Even the ones that were affiliated with the Islamic regime were different in the way they behaved or practiced their authority. One of the students in my private class was Orthodox Muslim, but she was very much against the regime. She had been in the regime’s jail. So for Iran religion is not the main issue, politics is. The Islamic regime has confiscated our religion and is using it as a political ideology, as a way of maintaining power and control. This is not the religion of my parents and grandparents, teaching love and tenderness and also tolerance. My grandmother, who never took off her veil, who was an Orthodox Muslim, would cry and say that this is not Islam. Muslims don’t flog girls to force them to wear the veil. The veil should not be mandated. I think as I was writing Reading Lolita I discovered that it was not so easy to divide people into heroes and villains. You could consider yourself a hero and become a villain at the drop of a hat. I don’t know if you remember the scene in Reading Lolita when one of the guys who belonged to the militia poured gasoline over himself and set fire to himself—when that happened, I thought Oh my god, I am called an apostate and yet here I am, healthy, standing in my classroom, teaching Henry James, and this guy who supposedly belongs to the regime, just killed himself in this manner. So, it not only made me empathize with him, but it made me understand that “they” too had their moments of frustration and grief, that not all of them were happy with the way things were going. I decided that I have to look at each case. I cannot just color everyone with the same brush. I have to understand that there are many colors and there are many ways of interpreting religion. Islam, like Judaism and Christianity, has so many denominations. So many interpretations. We should not take the most extreme interpretation and make it the whole Islam, which is what has been done in the West. This was one reason I wrote my book. I wanted to show the diversity of Iranian society. We, like anywhere, had people with different religions and beliefs, even had atheists and agnostics. And as for Islam, there were many different denominations and interpretations of it.

RR: Relating to that point, when you were talking about the value of literature, you spoke about the “shock of recognition” that can bring people together despite vast differences. We were just discussing how we need to have this more spacious understanding of other people’s experiences. How do those ideas connect with being able to recognize another person’s humanity, and with being able to recognize the validity of the variety of human experience?

AN: That is very important— empathy. That is so neglected right now, in our own country and around the world. We have a war in Ukraine going on as we speak. How do we confront this? One reason I have been focusing on fiction is that through knowledge and imaginative knowledge we find one way of confronting this lack of empathy. Obviously, you can’t travel to all parts of the world. You cannot know everything. You cannot even know everything about the country you live in. Through reading, and through discussions and debate, through knowledge, you put yourself in the experiences of people you have never seen. That is what literature is all about. I don’t know about your experiences at the university, but one thing that sometimes bothered me was that everybody would look at me and say, “You’re a woman and you’ve come from a Muslim majority country, so you write about women and Muslim majority countries.” And I would jokingly say, “No, I want to write about dead white males.”

Literature is about the Other. It is so boring to constantly think about yourself. To constantly write about yourself, constantly read about yourself. Obviously you have to read and think about yourself to some degree—for that, we have to use all our power to get more diverse people into positions where they can read and think and write about themselves. That is one of the things that we should be doing, but once we start writing and thinking and reading, then Others come into it. You have to allow the Others to come into your territory, to your domain. So, one way of fighting that indifference and creating empathy is through knowledge. That is why education becomes so important, from early childhood stories. They make us go places we haven’t been to and meet people who we have never known before. I hope that we will have serious changes in our education system. I hope that this generation would not accept things as they are and would rise up.

TP: How has Read Dangerously connected to your greater body of work, specifically with your other memoirs? What about this moment particularly necessitates a reflection on radical and progressive literature from the past?

AN: It is a very different book, partly because of the topic I was grappling with. I hope this book is not the type of book that preaches to the readers how to do things, how to think. I hope this book will place the reader within certain experiences, and through those experiences, it will draw out ideas and reactions. When I was writing Reading Lolita or Republic of Imagination, the books I chose were the books that fit the subject matter. Of course, they were my experiences. When I was in Iran, I was an English teacher. I was teaching the books that I had access to. We didn’t have access to many books over there. In this one [Read Dangerously], all of the books are about turbulent times. That is the main difference between this book and the other books. Otherwise, this book is a sibling to Reading Lolita and Republic of Imagination. One was about the totalitarian mindset, the other one was about the democratic mindset. This one is about the clash between the totalitarian and the democratic mindset, and how we go about it.

RR: I’m sure you recommend the books in Read Dangerously, but are there any other books that you recommend as either an accompaniment or books that have further developed the ideas in Read Dangerously?

AN: On my reading list there is a book called Twilight of Democracy by Anne Applebaum. I am also reading this book called The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry written by women. Women in the Persian language play a very important and revolutionary role. They have been writing for a thousand years. I use that to show how at each period, women refuse to become victims and define themselves, rather than be defined by others. There is a children’s book that I love by this great illustrator Peter Sis. He is beautiful in his portrayals. Although he writes children’s books, I love his books. I read them all the time. This one is called Nicky & Vera. It is about the true story of a man, who during the Holocaust, rescued lots of children. I am always very promiscuous when it comes to books! There are so many books that I could recommend, but these are the ones that come to my mind right now.

Read Dangerously: The Subversive Power of Literature in Troubled Times is available for purchase through HarperCollins.

Portrait by Leonardo Cendamo.