“How art can be delicate, and art can be strong. How delicacy can be a strength. How this can be true of people too. Did I learn this from Gladys?”

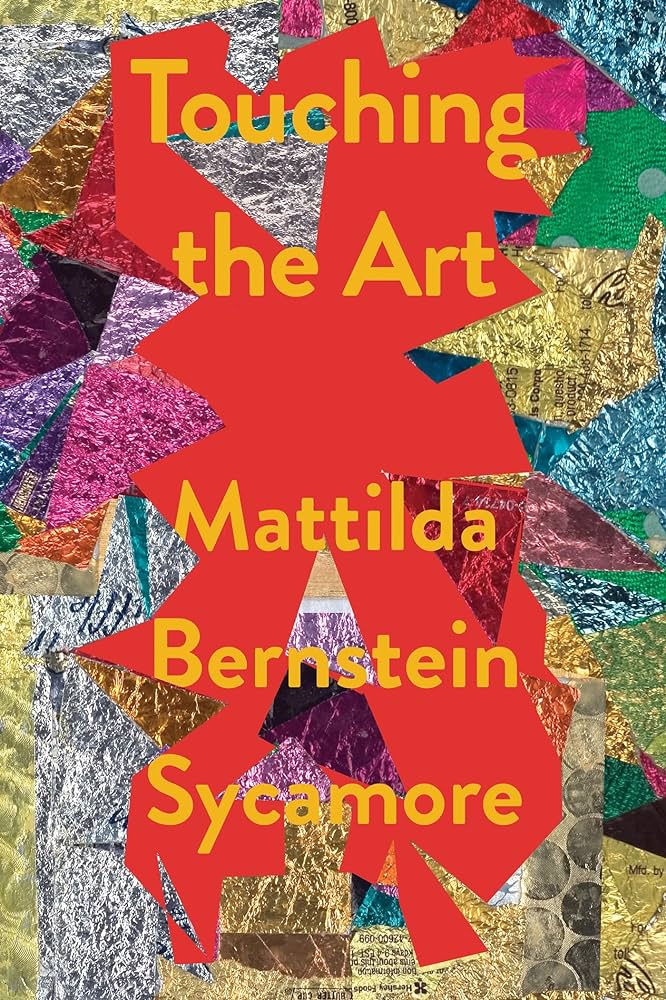

Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s Touching the Art moves deftly between memoir, art criticism, history, essays, and theory — always considering where art, and the body’s relationship to it, lives within the work, within a sentence. Consistently self-aware, Sycamore declares she wants “a history of everything left unsaid. Everything that never happened, but should have happened;” in directly lyrical prose, she builds those histories in front of us.

The book is ostensibly about Sycamore’s relationship with her paternal grandmother, the mid-century abstract expressionist Gladys Goldstein. Gladys, as we learn early on, was the first nurturer of Sycamore’s artistry — “When I was a child, Gladys told me creativity meant everything. I believed this myth, and it saved me,” she writes. Yet her betrayal underlies the work’s deeply affectual, genre-bending prose: when Sycamore leaves college to explore the queer avant-garde of San Francisco and her work turns to openly embrace queerness and gender non-conformity, Gladys calls it, and her, “vulgar.” Soon after, when Sycamore remembers and confronts her family about her childhood sexual abuse at the hands of her father, Gladys holds family meetings in her home with a false-memory specialist in full support of her son.

“Gladys divorced her first husband at age twenty, in 1937, in the midst of the Depression, leaving a life of guaranteed wealth for something precarious.

She knew she had to save herself.

To become herself.

When I was nineteen, I dropped out of college and moved to San Francisco.

To save myself.

To become myself.

Did this destabilize Gladys so much because it reminded her of her own choices?”

We arrive at this personal history decades after both these events; both Gladys and Sycamore’s father have passed, and Sycamore has transitioned genders. She is back in her hometown, living in Gladys’s house, walking the buildings where she taught for decades, living in the wake of hundreds of her works. In turn, Sycamore opens up Gladys’s life for us through memory, correspondence, and critique; we experience it as she does. She takes us on long walks through museums, occasionally slipping into art criticism as she considers how Gladys’s work fits in. Gladys grew up in Baltimore and rarely left — Sycamore tells us she returned to Baltimore in order to write this book, to investigate their shared history. The work is as much a memoir of Baltimore across a century as it is of a family within it. She tells us of Baltimore’s segregation and redlining, its position in the mid-century abstract art scene and academy, never losing sight of how Gladys stands in relation to it and to the larger canonization of abstract expressionist artists. Thus these tangential histories do not read as extraneous or perhaps even as tangential, only as necessary engagements with the breadth of Gladys’s life, of how a person affects others and the spaces they live and work in.

The formally traditional, quotidian, memoir Sycamore could be writing is subverted intrinsically by her prose style, one that is able to move between the public and private, the family and the city, the past of the present, and her and Gladys with sudden subtlety and deep empathy. Her whole being is considered; there are prosaic interviews with others who knew her, excerpts of letters between her and Sycamore, entries from both of their diaries. Sycamore brings an academic yet empathetic lens to her own history, reconstructing moments and years but allowing the fuzziness of memory to take hold. She presents these almost as archival documentation, yet we can never leave her subjectivity for too long — between the deeply personal and the historical, we are left questioning how people, and the life-giving art they create, are turned into history.

This, too, Sycamore addresses. In loose form, Sycamore runs head-on into Gladys’s racism, her complex relationship to gay male artists, and her (dis)engagement with the avant-garde — all of it, of course, intrinsically woven into their relationship. She narrates her way down into rabbit holes of research, leading us through a decades-long search of how a woman whose art hinged on formal creativity was nevertheless so invested in the trappings of middle-class normativity. What we receive, in turn, is a work that resembles stream-of-consciousness yet is far more considered, more purposeful in its relationship to the type of stories that are often left untold.

“If one doesn’t want to be one’s own history, does it become someone else’s?”

The self-consciousness woven through the memoir can threaten to subsume the reader — but on more formally experimental pages interwoven between longer, essay-like pieces, Sycamore gives us space to consider the word, and especially the sentence, as one would experience the artwork she engages with. Grief, constantly complicated by their relationship and rarely addressed by name, fills the blank pages; perhaps in addition to all the forms the book claims to live between, elegy is the most apt. Gladys, however, is always talking from beyond; the work, endlessly empathetic, wants her to — but it’s never shy about pushing back.

In a work with a knowingly slippery relationship to structure and form, it is hard to feel an impetus pushing through. Instead, we follow Sycamore, contemplative and poetic, through annals and anecdotes, discursions through the works of other artists, poets, the life of Billie Holiday — until she tells us it is time to stop. Near the end, she tells us that she could have easily written and researched much more, investigated every aspect of Gladys’s life and art, but that “telling the definitive story reveals that the story can never quite be definitive.” She leaves us where we started, musing on Gladys’s pieces that now hang in her home, forever figuring out how to live with art and history, which, of course, is about living with and without others. “There is always more to art than art,” she writes, “but you can’t wonder too much about what has been lost, or then there will only be loss.”