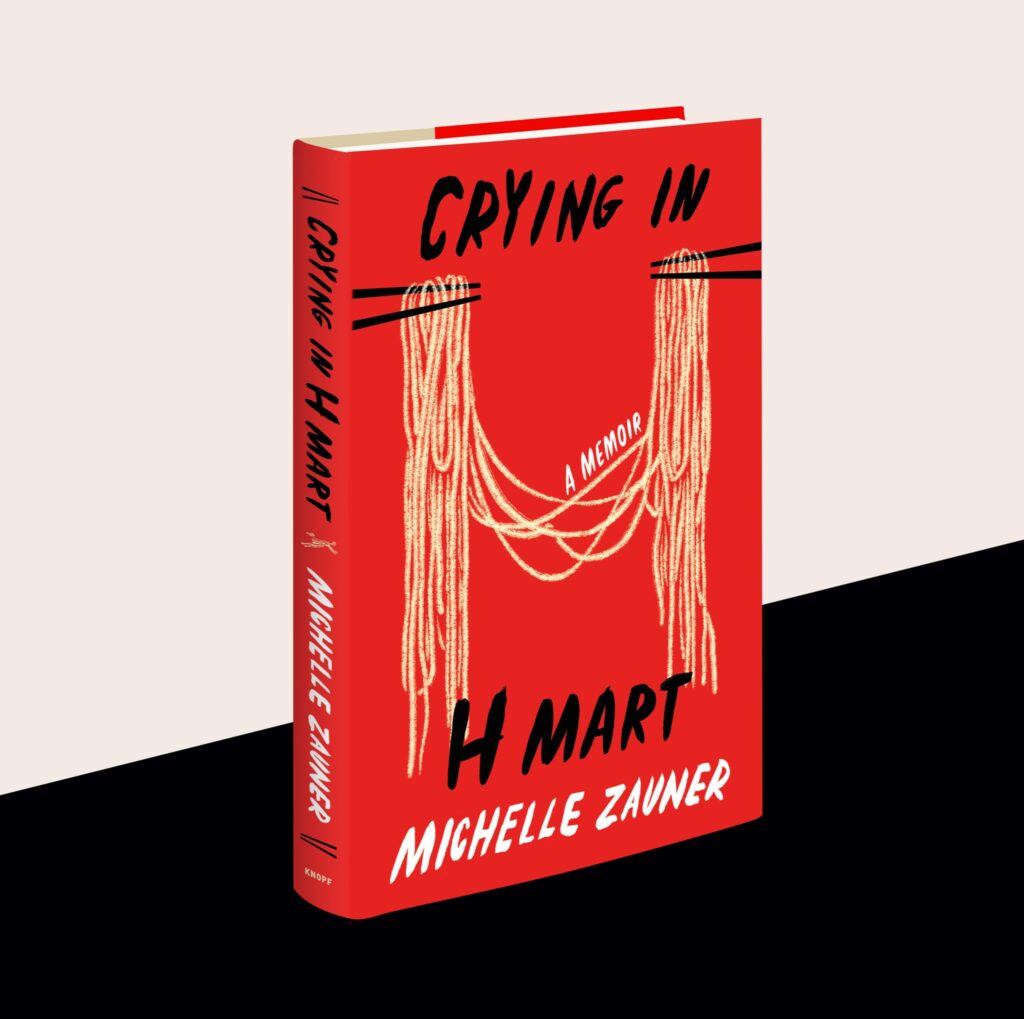

Michelle Zauner is a writer and musician who performs under the alias Japanese Breakfast. CJLC’s Annelie Hyatt spoke with Michelle about her stunning memoir Crying in H Mart, published on April 20th, 2021, and her forthcoming indie rock album Jubilee, which is set for release on June 4th, 2021. Thumbnail image by Valerie Chiang.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

May 18th, 2021, 11pm.

Annelie Hyatt: I wanted to discuss a really beautiful scene in Crying in H Mart, when you and your dad went to Vietnam and had an argument during dinner. There was a moment where you looked at your dad after the argument and had a stunning observation about his thinning hair. You write, “It felt like just another thing he’d been cheated out of, and I got to thinking he really had been cheated his whole life in a way I had never experienced and could maybe never comprehend. Cheated out of a childhood, out of a father, and now he’d been cheated again, robbed of the woman he loved just a few years shy of their final chapter.” Despite being currently estranged from your father, you still treated him with tenderness and generosity. You do the same with Kye, someone who came to care for your mom. In your music, too, you are stepping into the minds of others, from a billionaire in “Savage Good Boy” to a teenage boy in “Kokomo, IN” who pops wheelies while he waits for his significant other to come back to him. How and why do you center empathy in your work? What does empathy mean to you?

Michelle Zauner: I’m very fascinated by people and how we interact with one another, and how we hurt one another. And, while in some ways I’m not great at it, I spend my whole life trying to understand people. As an artist, what you’re trying to do is get a better understanding of people.

In writing nonfiction and in writing [Crying in H Mart] it helped me to understand these people in my life by presenting them fairly. I tried to present them generously. In the process of writing this book, I was able to forgive in particular Kye and my dad, whom I was very angry at for a long time. I don’t think that nonfiction is successful if you don’t treat yourself as a protagonist with the same amount of criticism, with as much of a critical eye and judgment. It’s necessary to present your shortcomings in the same way that you present others’.

That was a real challenge for me. In the first draft, I would present some people pretty cruelly because I was so angry at people in my life. In the beginning, I had a really angry rant about my uncle who had nothing to do with the story, which was unnecessary. Sometimes it takes writing and having time away from [the situation], and then going back in and adjusting to make great art as a more mature person. I don’t know if I was necessarily successful or not, but that was absolutely what my aim and intention was. There were certainly things that I kept out of the book because they were better left unsaid.

In terms of my fictional songs, while I don’t necessarily sympathize with billionaires, I think that what makes villainy so terrifying is that you can see parts of yourself in their behavior. I’ve never had that amount of wealth, obviously, but I think that greed, bad behavior, and placing yourself above others are things that everyone can relate to. That’s a scary thing. What makes a villain scary is that you can see what could happen if you don’t reel in parts of yourself—that that could be your future.

The art that I really enjoy and try to make is art that blurs the line between villains and protagonists. [This kind of art] demonstrates that people whom you think are the villains have some really redeeming qualities and that people whom you think are heroes have some major flaws. That’s just human nature.

AH: I wanted to turn to the differences between producing art and producing writing. I know that you direct and sometimes edit your own music videos, and so I assume that you have a little more control over the music that you produce than the writing than you produce, which goes through different stages with an editor who tells you to cut down things that were too extraneous. How did you deal with that loss of control?

MZ: I never felt that I had a loss of control, actually. The process was very different from when I worked with publications before. Certain publications destroyed me, but I didn’t feel that way when writing Crying In H Mart. In my book, I felt like I had an incredible amount of control. Pretty much every suggestion that my editors made was something that I wholeheartedly agreed with.

The suggestions were never anything unusual but more of a copy-editing thing. I never bristled at anything my actual editor sent over, because they were often broad suggestions. For example, one thing that my editor suggested was writing more about the weather, because it would put the reader in the time and place better. That profoundly impacted my writing.

At first I thought, “What do you mean, write about the weather?” But then I read Richard Ford’s Rock Springs and Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping, which are books that I reread probably every year, and just underlined all of the sentences about the weather. Then, I went through my book and noted where the pacing needed something and started inserting moments about the weather. And I feel like [the book became] better because of it.

Another edit that my editor suggested was, “I feel like we need to know more about Oregon, and I really want to know more about Oregon. I want to see it.” It’s really important to have the perspective of an editor, especially because it’s a memoir. Sometimes everything is so obvious to you that you don’t consider that people who are reading this won’t know what Oregon looks like, and that you need to explain it to them.

She also mentioned that “It feels like you’re really angry at your father. And we don’t know why.” Part of the reason why I had to go back and be a little more generous and fair to him was because I knew all along that I was very angry. This person had read this book and felt that too, and I needed to put in more information about why I was angry, as well as put in more information that bolstered his character so that he could withstand that.

While I didn’t feel a major loss of control when writing the book, I did feel a major loss of control when submitting for magazines. There are a couple magazine editors that definitely butcher the shit of your writing [in a way that] made me extremely uncomfortable, but it feels very different in the book writing process.

I really loved it. It wasn’t as if I was up against anyone. One thing that I didn’t want to do was italics. I hate it when non-English words are in italics because it makes it seem exoticized. It’s as if you’re supposed to be reading it in this gross slam poetry kind of voice. Some people have told me that it felt empowering to see none of those words italicized, and I’m just really lucky to have wonderful editors [and have] this time period now where there aren’t people that are going to force that kind of thing onto you.

AH: You’ve talked about rereading some books regularly. What are your literary inspirations and do they align with how you write? Or are there crucial differences?

MZ: Yeah, I feel that those, [Richard Ford’s Rock Springs and Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping], are the two main ones. I also love Lorrie Moore.

I read a lot of short fiction in college and that stuck with me—Carver, Salinger, Roth, Tobias Wolff, you know. I also read a lot of realist writers, because I was largely raised by [English as a Second Language] parents. Neither one of them went to college. So I was never going to be a beautiful, verbose, writer. I was never going to write like Proust. So I felt comfortable with writers like that, because it felt like they were very plain spoken. Of course, Marilynne Robinson, at least, is definitely fancier, but she’s plain spoken and smart in a different type of way. They can find meaning in very ordinary blue-collar kinds of people and moments. And that kind of writing has always stuck with me and is what I’ve always been interested in doing myself.

AH: I know a lot of people who grew up with people who are English professors. I remember that, as a kid, I was super jealous because my family is very STEM-oriented—my dad is a computer programmer.

MZ: Yeah, definitely. My dad was a truck broker.

AH: Exactly. How did you navigate not having a literary background?

MZ: I was really insecure about it. I felt as if someone had laughed at me about it before. Music as a type of storytelling felt very within reach, because you don’t need any real education. The role models that you have in music were “literary” in a way that wasn’t rooted in any type of education.

I don’t think that I grew up with a book in my house that I didn’t request. My parents didn’t really read. We had some Tom Clancy novels sometimes. My parents never recommended anything to read, so I felt like such a late bloomer in a way. And luckily, I had a wonderful professor in college that really changed my whole life—Daniel Torday at Bryn Mawr College. He took his students very seriously, and he’s just a great teacher. What I read in that class are all the writers that I mentioned. They just stuck with me. I took every single one of his classes that he offered except nonfiction. I was lucky that I had a professor who took me seriously and never made me feel that [lacking a literary background] was something that would keep me from exceling creatively.

AH: I wanted to ask about another way in which songs and books are different. I watched your interview with Ben Gibbard, and you two talked about how songs are an affordable way to access a certain emotion, as books and films take a bit longer because you need to watch the entire thing or read the entire thing. Why did you decide to make Crying in H Mart a book instead of a film or a concept album? How is it different for people to listen to your music about your mom compared to reading your book?

MZ: I mean, the whole process happened in stages. I wrote Psychopomp around the same time that I wrote the nonfiction essay, and they just gave me different things. I feel like music is just a pure feeling. There’s a limited amount of space to express that feeling verbally. In books, you have more room and space to investigate things. You can dive deeper into the characters in your life. That was exciting for me, and just naturally what I was drawn to.

I do think that they offer similar things to people that interact with them. Music is so impressionistic, and there’s different ways to interpret it. Whereas you have to really guide someone along so that they feel what you them to be feeling in a book.

AH: Japanese Breakfast toured with Mitski. She has this interesting quote about art, where she pushes back against the notion that her art just comes out of her, that it spills out of her without any sort of meaning or intention. She emphasizes the authority she has over how she releases her art into the world. How do you release your art into the world—is it something that comes out of you or does it undergo a lot of refinement and revision?

MZ: I really love Mitski. Before I was on the Daily Show, I watched Mitski thinking that it would make me feel more comfortable. But it just made me even more nervous, because she’s so well spoken, whip smart, and so funny. I was like, “Goddamnit, Mitski!”

I really love the way that she talks about [art]. I wish that I could put it as well as she does. For me, to be honest, it’s a little bit of both. I think that’s what making art kind of is: there is this part of you that creates this raw source material that flows out of you, but it would be total garbage if you didn’t spend a lot of time and develop your craft and revise it into what ends up being out there in the world.

I think that the frustration with that is that it’s this very gendered thing. There is this notion that women in the arts have to really unpack and present their trauma, and everything has to be fevered and emotional. Men get asked all these questions about their craft, their influence, and their reference points. So, I think that’s the frustration. But, you know, on the flipside I’ve talked to men who have been like, “I wish that they would ask me more about my life and my feelings, and instead they ask me these more technical oriented questions.” There is this balance that needs to be found.

AH: Returning to our discussion about fictional songs, I wanted to discuss the fact you juxtapose intense and autobiographical songs about your mom. I’m referring to “Savage Good Boy” and “In Hell” in particular, which are right next to each other on the album.

You’ve spoken in other interviews about how your art comes from a deep fear of being misunderstood. How do your fictional and autobiographical songs relate to one another, and how do they help your listeners understand you as a person?

MZ: I’ve always done that in my albums. Albums really lend themselves to drifting in and out of fiction and nonfiction. Ultimately, I’m just really captivated by the human experience, and sometimes, there are certain parts of that experience that are best explored through nonfiction and personal experiences, and sometimes they are better explored through a fictional lens.

As I mentioned before, I’ve never been a billionaire coaxing a young woman to live with him in a bunker, but I have experienced greed and exhibited bad behavior and put my needs over others. I’ve never been in a small town in Kokomo, Indiana saying goodbye to his teenage girlfriend, but I have grown up in a small town and know what it’s like for a relationship to end before you’re ready. I’ve never been a woman posing in bondage waiting for someone that never comes home, but I have definitely been emotionally needy and felt that unrequited desire.

Sometimes, it’s boring to present the truth. I mean, if the song was like, “My husband is ignoring me today and I’m upset about it,” that would not be a good song! But if it’s about a woman who is done up and drunk in bondage, waiting for a lover that never comes home, then that’s a striking image. That can target the things and themes that everyone goes through.

AH: Have you ever read The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien?

MZ: No, I haven’t.

AH: It’s good—I really enjoyed it. There’s this quote in it about how sometimes, false things are even more true than true things.

MZ: Totally. I think that sometimes you can definitely be braver about those things. I don’t always want to talk about my bad behavior.

AH: I wanted to talk about your desire to be a neutral body in writing, and how this was a driving force in your resistance to nonfiction because it felt hard to be a neutral body when you’re a person of color. After publishing your book, how do you feel about neutrality? Do you think that neutrality is possible in art—if so, what role can it play or should it play?

MZ: I don’t know if it’s ever possible for us [as people of color]. At least in my life. Maybe in the future—the younger generation is pioneering some really incredible stuff.

It’s incredible that my book about mixed race identity debuted at #2 on the New York Times bestseller list. That’s amazing. But, I think that the nature of being a minority is that you always have to explain something. You’re on the margin.

Sometimes, I forget because I feel like a neutral body, because I’m myself. Sometimes I forget that when I’m writing, I need to [specify that I’m talking about] my Korean mom. I would write, “Ever since my mom died, I started going to H Mart to preserve my heritage.” Then I’d remember, “Oh, my Korean heritage.”

You can always introduce a character, and then everyone will assume that they’re white unless you create some sort of descriptor. People don’t like, for example, when I call my dad a Caucasian American. It makes people weirdly uncomfortable. Because if I just said that he was an American guy, I’d be promoting the assumption that all American people are Caucasian. Why are people so uncomfortable when I announce that he’s white or Caucasian, when I always need to put that description for my mom, who was also an American, that she is Korean? It seems unfair to me.

I find that people are really uncomfortable with that, and that’s why they feel that they have to mention that my father was Jewish—which he really wasn’t. I have Jewish heritage, but he’s not Jewish. He was not a Jewish man, but I think that people have started to do that because they don’t feel comfortable.

It’s frustrating—when I’m so passionate about something, I can’t really get my words together. But no, I don’t know if I’ll ever see a future [where neutrality in art exists]. My book is always going to be an [Asian American and Pacific Islander] book. And it is an AAPI book, but it’s also a book about mothers and daughters. Wild isn’t a Caucasian book, you know what I mean?

Even answering all these questions about the Asian Americans and anti-Asian American hate crimes—why is that labor on me? If there’s a shooting on Caucasian people, why aren’t we asking writers about those shootings? I don’t understand.

I’m just so hungry to be treated—I don’t want to be in your campaign this month, because you want to celebrate AAPI month. I got this email recently that said, “Oh, I thought of you to be a part of this panel, this AAPI thing.” I thought, “Why don’t you just think of me when you need an artist?” There’s always going to be this frustration about [being grateful] for this opportunity… for my community. I love being Asian American, but there is this real frustration that no one is ever going to fully feel like I’m here based on merit. They’re always going to think that I’m filling a diversity slot, or that they’re doing me a favor in some way. I hate the idea that people are feeling good about themselves reading my book, as if they’re contributing to stopping Asian hate by reading it. I don’t want that on me.

Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner available from Penguin Random House. Jubilee available for pre-order on Bandcamp.